"He wasn't," she snapped. "Khrushchev had roaches in his head."

That could explain a few things.

Posted on 02/28/2014 7:52:21 PM PST by annalex

Russia’s paradise lost belongs to Ukraine—and that’s where the trouble begins.

By Cathy Newman

The past is never past in Sevastopol. It waves from flagpoles and drapes the parade stand on patriotic holidays. It finds sanctuary in war monuments and is posted on signs: Lenin Square, Heroes of Stalingrad Street, Cinema Moscow. It even simmers in a pot of borscht.

Take Galina Onischenko's version of the eastern European staple. "This is Russian borscht," she said, setting down a porcelain bowl of "green" or summer borscht with its dill-flecked mosaic of beets, carrots, and potatoes. "No lard with garlic like they put in Ukrainian borscht."

Galina, a 70-year-old grandmother with a cumulous cloud of white hair and stern, cornflower blue eyes, had returned to her fifth-floor walk-up from marching down Lenin Street waving a Soviet Navy flag in support of her beloved Black Sea Fleet. "Sevastopol is a Russian city, and we will never put up with the fact that Ukraine is in charge," she said.

Though Galina would protest, borscht, according to Russian food historian V. V. Pokhlebkin, is originally Ukrainian. Though Galina protests, Sevastopol, a city in Crimea, is Ukrainian too.

The Crimean Peninsula is a diamond suspended from the south coast of Ukraine by the thin chain of the Perekop Isthmus, embraced by the Black Sea, on the same latitude as the south of France. Warm, lovely, lush, with a voluptuously curved coast of sparkling cliffs, it was a jewel of the Russian Empire, the retreat of Romanov tsars, and the playground of Politburo fat cats. Officially known as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, it has its own parliament and capital, Simferopol, but takes its orders from Kiev.

Physically, politically, Crimea is Ukraine; mentally and emotionally, it identifies with Russia and provides, a journalist wrote, "a unique opportunity for Ukrainians to feel like strangers on their own territory." Crimea speaks to the persistence of memory—how the past lingers and subverts.

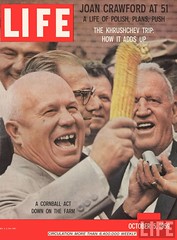

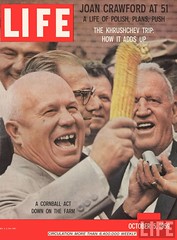

In 1954 Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, signed Crimea over to Ukraine as a gesture of goodwill. Galina was 14 at the time.

"Illegal," she said, when asked about the handover. "There was no referendum. No announcement. It just happened."

What was Khrushchev thinking?

"He wasn't," she snapped. "Khrushchev had roaches in his head."

Crimea was a lovely present, but the box was empty. Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union anyway. "My parents discussed the transfer, but we weren't concerned," Galina said. Moscow was still in charge. No one could have ever imagined the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, when Crimea would be pulled out of the orbit of Russian rule along with an independent Ukraine.

Do you miss the Soviet Union? I asked Galina, as she reminisced about the stability of life under the Soviets. Prices were artificially low. "You could get a kilo of sugar for 78 kopeks," she said. "Butter, only 60! Now, I don't even buy it." Education and medical care were free. As for a vacation: "I could go to a resort"—now completely out of the question on her monthly pension of $130.

"Yes, we have a longing for the Soviet Union," she said. "But it cannot come back, no matter how much we wish. We can only toskavat."

Toskavat, verb, to long for. Toska, noun, a longing, darker than nostalgia, verging on depression. Russian culture is embedded in a matrix of toska. When in Three Sisters, by Anton Chekhov (who owned a dacha in Crimea), Irina wistfully says, "Oh, to go to Moscow, to Moscow!" that is toska. If Sevastopol, where 70 percent of the population is ethnic Russian, could talk, I imagine it too saying, To Moscow, to Moscow. In a 2009 poll by the Razumkov Centre, a top Ukrainian think tank, nearly a third of the Crimean respondents said they wanted their region to secede from Ukraine and become part of Russia.

In some ways it still is. But not just Russia. Crimea is practically a throwback to the old Soviet Union: the Early Concrete Bunker style of architecture, the rusting hulks of Russian warships in the harbor, the hammer-and-sickle medallions on the iron gates of Primorsky Park. It's also attitude. Brusque, rigid, humorless: the worst kind of Soviet hangover. You can take Crimea out of the Soviet Union; to pry the Soviet Union out of Crimea is something else. When I asked Yelena Nikolayevna Bazhenova, director of a Sevastopol-based tour company, why Crimea with its lovely seaside didn't attract more tourists, she hesitated. "We are not accustomed to greeting people with a smile," she finally said.

Crimea also sounds Russian. Ukrainian may be the official language, but Russian is the lingua franca, even in city hall. Of 60 secondary schools in Sevastopol, only one holds classes completely in Ukrainian.

A quirk of history had swept Crimea away from Russia, leaving Moscow with its own share of toska. As a former Russian deputy foreign minister told Steven Pifer, a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine: "In my head, I know Ukraine is an independent nation. In my heart, it is quite another thing." An inventory of Russian forfeiture in Crimea: the vineyards of Massandra and Inkerman; champagne the color of rubies; Yevpatoriya and Feodosiya, the briny health resorts of the west and east coasts; sun-bleached Yalta and Foros on the south coast; orchards heavy with peaches, cherries, and apricots; fields tawny with wheat.

Finally, harbors that never freeze. Unlike Russia, Crimea has the blessing of warmth. Sixty-five percent of Russia is covered in permafrost. None of Crimea is. A fifth of Russia is above the Arctic Circle. None of Crimea is. In February, when it is 14°F in Moscow, it can be 43 in Yalta. "Russia needs its paradise," Prince Grigory Potemkin, Catherine the Great's general and lover, wrote in urging annexation. Nearly every European power had carved slices of Asia, Africa, and the Americas for their imperial platters; Russia was no different in its appetite to expand. In 1783 Catherine declared Crimea to be forever Russian, adding 18,000 square miles to the empire, extending its border to the Black Sea, paving the way for its rise as a naval power. Russia had claimed its paradise.

And kept it for 208 years, until the collapse of the Soviet Union. With the emergence of newly independent states, assets of the former empire—including its military bases—became the property of those states. But Catherine's prize was not readily relinquished. Russia had few cards to play, but one strong hand.

"We were seriously dependent on Russian gas and oil," explained a Ukrainian official. "Our debt to Russia was about a billion U.S. dollars. The pressure was terrible." The two nations brokered a deal in 1997. The fleet could stay until 2017. Ukraine was credited tens of millions of dollars against its debt. Last year the pro-Russian government led by newly elected President Viktor Yanukovych extended the lease for 25 years. Again, gas and oil were the lubricants. In exchange, Russia gave Ukraine, still drowning in debt, a 30 percent discount on natural gas.

Reaction was split, as usual, between the Russian-speaking east and south of Ukraine and the western regions, where Ukrainian nationalism runs strong.

Galina was pleased. The Russian Navy is in her genes. "My grandson is in the St. Petersburg military academy. My husband was a naval officer. My grandmother sewed sailor uniforms. I grew up in a house of heroes in a city of heroes."

A city of heroes, a shrine to war. There are 2,300 memorials in Sevastopol; the city itself is practically bronzed. In 1945 it was awarded the Order of Lenin by the Soviet Union and named a Hero City for enduring a 247-day siege by Germany in World War II. Nearly a century earlier it suffered a 349-day siege by French, British, and Turkish troops in the Crimean War.

A cautionary note: Crimean history would suggest that it is folly to think that possession of any place, especially paradise, is anything other than a tenancy. Crimea has passed from hand to hand, from Scythians to Greeks to Romans, Goths, Huns, Mongols, and Tatars. The latter, Turkic Muslims who migrated from the Eurasian steppes in the 13th century, were brutally targeted by Joseph Stalin and suffered mass deportation.

For three days in May 1944, Soviet militia pounded on Tatar doors, rounded up families, ordered them to pack, and expelled them to Central Asia—some 200,000 in all. Nearly half died from illness or starvation. "I was a young boy the night they came," said Aydin Shemizade, a 76-year-old retired professor from Moscow. "I remember reaching for my book bag hanging on the wall. A soldier ripped it out of my hands." His voice cracked. It was 20 years before he saw his homeland again.

In 1989 Mikhail Gorbachev allowed Tatars to return to Crimea. About 260,000 have done so, and they now represent 13 percent of Crimea's population. Many live in squatters' shacks on the outskirts of Simferopol and Bakhchysaray, hoping to reclaim their ancestral lands, haunted by dispossession and neglect. Even so, Tatars are largely pro-Ukrainian. They fear Russia reflexively—because of its nationalism and because it is the successor to the Soviet state—but Ukraine has no such baggage.

"Conversation about Crimea was constant in my family," said Rustem Skibin, a 33-year-old Tatar artist with the hooded eyes and intensity of a falcon. We sat in his studio in back of his house in Acropolis, a village northeast of Simferopol, where the green of coastal Crimea gives way to the long horizon of the hot, dry steppes. "I heard the stories," he said, "but I didn't feel them." The family had been forcibly resettled in Uzbekistan. "In 1991 we came back. Crimea was home. I went to Alushta to see the narrow streets with their small Tatar houses. I felt a sense of belonging and understood what it meant to be Tatar in my homeland."

It is our motherland, I kept hearing, but whose motherland? For Galina Onischenko, the motherland was Russia. For Rustem Skibin, Crimea was the Tatar homeland and had been for at least seven centuries. For Sergey Kulik, 54, formerly an officer on a Russian submarine and now director of Nomos, a Sevastopol think tank, the motherland was Ukraine.

"I was sorry when the Soviet Union collapsed," Kulik admitted over dinner one night. "Suddenly I was nowhere. I had to adjust."

As a naval officer, Kulik had lived comfortably under Soviet rule, but the collapse inspired an epiphany. One could live a cushioned life and still be surrounded by repression, brutality, and falsehood. "I too have nostalgia, but it is not blind," he explained.

When Ukraine became independent and took over Sevastopol (a closed city under the Soviets; entry required a permit), both governments faced the task of dividing up the Black Sea Fleet. Kulik and his fellow sailors—there were about 100,000—had a year to decide between the Russian and Ukrainian Navies.

"I didn't think twice," Kulik said. "I am Ukrainian. My parents are here. I speak Ukrainian. So I chose the Ukrainian Navy." But what does it mean to be Ukrainian? I asked.

Kulik thought a while. "Being Ukrainian is like breathing," he answered.

It seemed important to keep asking.

"In the 21st century it's all about political boundaries. If you consider yourself to be Ukrainian, you are," said Olexiy Haran, a political science professor.

"To be Ukrainian is the cherry trees in blossom, the ripening wheat, our stubborn people who work so hard, and the language I love," insisted Anatoliy Zhernovoy, a lawyer and member of the Ukrainian Cossack movement. The Ukrainian Cossacks, whose forebears patrolled the steppes from the 13th to the 18th centuries, represent a muscular revival of national identity.

"The era of nationalism is past. To be Ukrainian is to be a citizen of Ukraine. That's it," said Vladimir Pavlovich Kazarin, the president's representative to Crimea in Simferopol.

But Sergey Yurchenko of the Crimean Union of Cossacks disagrees. His paramilitary group of about 7,000 men consider themselves defenders of Russian nationalist ideology. I met Yurchenko at a Cossack compound an hour's drive from Sevastopol, where in a month 200 boys 12 to 15 years old would attend summer camp and receive military-style training, which he'd supervise. Yurchenko wore a beret and battle fatigues and had the face of a pugilist who'd taken too many punches. He showed me the field where the boys would live in tents. "We teach them patriotism," he said. They'd also be taught martial arts and how to shoot machine guns.

The camp was in the shadow of a 16-foot-high wood cross Cossacks had hauled up to the top of Ay-Petri Plateau. Government officials had demanded, unsuccessfully, that it be removed because it offended the local Tatar population. "You may have noticed, there are many Tatar squatters in the area. We keep an eye on them," Yurchenko said. "The Ukrainian government turns a blind eye. It's up to us to keep things in line." Keeping things in line included several fights in 2006 between Tatars and Cossacks at the Bakhchysaray market. "We don't wait for court orders to act," Yurchenko said of the violence that sent dozens to the hospital.

"He's a provocateur," Refat Chubarov, deputy of the Mejlis, the Tatar parliament, said at the mention of Yurchenko's name. "We're worried about any paramilitary movement, but the fact that kids are taught to play with guns is not nearly as important as the ideas they are taught to play with."

On one of those balmy summer days Slavs must dream about in winter, I sat in a restaurant in Balaklava with Konstantin Zatulin, a Russian Duma deputy. Zatulin, persona non grata in Ukraine during Viktor Yushchenko's tenure as president, was enjoying a warm welcome back under the new, pro-Russian regime. Our table overlooked the harbor where Russian submarines had once glided into port. Across the bay, beyond sleek white yachts at their moorings, you could see the dark mouth of a cavelike entrance to a four-acre submarine complex carved into the side of a mountain.

The Cold War relic, a top secret military installation under Soviet rule, was now a museum. Tourists could file past the 150-ton nuclear-blast-proof titanium doors, walk through tunnels, and peer into chambers where nuclear warheads had been stored. The deadly game of flinch between the two superpowers seemed far removed from the Crimean champagne a waiter was pouring.

"Deputy Zatulin," I asked, "do you know what Catherine the Great wrote Potemkin after claiming Crimea? 'Seizing objects is never disagreeable to us; it's losing them we don't like.'"

"Catherine wrote something else," he replied, looking at me steadily. "Potemkin suffered several defeats; he wanted to withdraw. Catherine wouldn't hear of it. 'To have Crimea and give it up is like riding a horse, then dismounting and walking behind the tail,' she told him.

"Well, we've given it away." He scowled. "The question is under what conditions it will continue to exist."

The same question was being asked in Kiev by the opposition. "Russia doesn't need its fleet in Sevastopol," a former minister of defense had said with barely suppressed anger. "It's just there to create instability."

Zatulin practically curled his lip when I quoted the former minister.

"The government that terminates the lease will have to answer the question of where to buy cheaper gas," he said.

Will the Russian fleet ever leave? I pressed. And when?

Zatulin, a man with a broad, florid face and thick build, picked up a red mullet from a platter of grilled fish and snapped its head off.

"My personal opinion? Never."

Write the truth, Galina kept urging—the Russian word is pravda—but truth wasn't easy to sound out, not with the colliding dreams of Ukrainians, Russians, and Tatars. Conventional wisdom held that violent conflict between Russia and Ukraine over Crimea was unimaginable because of close cultural and historical ties, especially now that Yanukovych had made Russia Ukraine's new best friend by extending the lease. It was tempting, but simplistic, to assume Yanukovych was Vladimir Putin's man in Kiev. The election had been fair, under the Yanukovych administration parliament had voted to take part in NATO military exercises, and Ukraine still hoped to join the European Union. Nonetheless, uneasiness lingered.

"I was in Red Square in Moscow on Victory Day," Leonid Kravchuk told me. Kravchuk, Ukraine's first president, had deftly made the transition from Communist Party boss to leader of an independent democracy. Now, resolutely Ukrainian, he was wary of the Kremlin. "I tell you, I have seen many parades in my day. I have never seen one like this." He meant the turned-up volume on the demonstration of power.

Worries that Crimea could be the next flash point between Russia and its former satellites had faded with the resetting of Kiev's foreign policy, but Kravchuk thought a replay of the 2008 conflict when Russia sent tanks into Georgia (to protect its citizens, said the Russian government, though some suggest it was a reach for power in former territories) was not out of the question. "Such a thing is still possible," he said. "Russia knows what it wants from Ukraine. Ukraine doesn't know what it wants from Russia."

The best immunity against Russian intrusiveness seems to rest on Ukraine's ability to solidify its sense of self, but the road will be rocky, given the struggling economy and weak political traditions. True, Yanukovych had extinguished the sparks between Ukraine and Russia, but did Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov really have to say, "Everything depends on the goodwill of Russians—we're like serfs." With public comments like the prime minister's it is small wonder that a national survey reported Ukrainians trust astrologers more than politicians.

On my last day in Crimea, I sat on a veranda overlooking Sevastopol Bay with Sergey Kulik, the Russian submarine officer turned Ukrainian think tank director. Across water the color of malachite, you could see the arc of temple-like government buildings rebuilt by Stalin after the war. "Sometimes when I get a visa to travel," said Kulik, "the consul looks at me as if to say, Are you coming back? Don't think for a minute I won't. I am Ukrainian. I will come back."

Kulik knew who he was. And the rest of Crimea, not to mention Ukraine itself? Identity is problematic, said Oleg Voloshyn, press secretary to the foreign minister, because Ukraine was not a classical nation like England. Though most eastern European countries were patchwork entities, Ukraine was more fragmented than most, split as it had been in successive centuries between Russia and Poland, Russia and Austria, then between Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, before finally becoming an independent state in 1991.

Crimea, it turns out, is as much a conundrum for Ukraine as it was for Russia. "Potemkin called Crimea the wart on Russia's nose," I reminded former Ukraine President Leonid Kravchuk at the close of our interview. Potemkin meant that Crimea was unruly; he worried Russia would never subdue the Tatars and gain control. "Instead of being the wart on Russia's nose, wouldn't you say Crimea is now the wart on Ukraine's nose?" I suggested.

Kravchuk thought a bit. "Not a wart. A festering carbuncle."

Perhaps it will take another generation—several, even many—before Crimea defines itself as Ukrainian and not Ukrainian by default. Resisting change are those like Galina. On my last visit she told me she'd spent 100 hryvnia to have a new Soviet flag made, despite her heating-bill debt of 1,500 hryvnia.

"My flags will always stay with me," she said. "They inspire me and keep my spirits high." She carefully unfolded the banner with the hammer and sickle paid for with her pension money. It was nearly as long as her couch.

She seemed suddenly frail, sitting in her dark apartment in a pair of mismatched slippers, surrounded by the past—her flags (six Soviet Navy flags, the tsar's flag known as the St. Andrew's, the newly acquired hammer and sickle banner), her grandfather's sword mounted on the wall, military medals, the sepia photograph of her husband in uniform, her father's sailor's tunic wrapped in tissue and mothballs.

"My great-grandfather, my grandfather, my father, my husband and son served in the fleet," she said. "And now, what do I have? A two-room flat and no money to pay for hot water."

The sword on the wall had tarnished. The sepia photographs were fading. The past, a political fairy tale of 78-kopek-a-kilo sugar and state-supported vacations, had vanished. The Iron Curtain had been torn down, and a nation was stumbling its way into the future.

"The sea is still with me, though," she said. "They did not take the Black Sea away. I can still go to the sea in the morning and swim."

It has to be asked what is in the interest of the Russian people in this context? We have to view the territories populated by ethnic Russians as shared by two peoples: the Russians, a small minority by now, and the Soviets. The latter is "the new socialist community of men" as the Khruschevite propaganda called them. And on that score, it was correct. I wish whatever remains of True Russia, the Russia of the Tsars, all the best. It is for that reason for Putin to fight for sovietized Crimea is not only to fight against the treaties that RF signed; it is not only aggression against the internationally recognized in the present, and presently violated, borders of the sovereign country of Ukraine; it is a further injury to the disappearing Russian nation dealt by the KGB.

If you want to be on this right wing, monarchy, paleolibertarianism and nationalism ping list, but are not, please let me know. If you are on it and want to be off, also let me know. This ping list is not used for Catholic-Protestant debates.

Its a very human story. You cannot but have respect for a widow from a family of military tradition.

Ukraine is less a country than a state of mind. It has what is called in Canada the two solitudes.

Its a bilingual country and needs to embrace its past and its dual heritage.

If Ukrainian nationalists insist on having it their way, they may be left with half a country and they’ve already lost, it appears, the Crimea.

>>Galina Onischenko’s<<

BTW, her name is ethnic-Ukrainian.

Russia can’t let Crimea go — not as a matter of geological reality.

“If Ukrainian nationalists insist on having it their way, they may be left with half a country and they’ve already lost, it appears, the Crimea.”

Half a country is better than no country.

We should respect any military wearing the uniform of their country. Less so a military wearing no identifying marks as was seen now invading the Crimea.

The Sovs do not deserve to be respected. They are an artificial pseudo-ethnic product of artificial selection of 1917-1991 that poison the land they step on.

That already happened when the Soviet Union, that recognized the present and persently violated borders of Ukraine, dissolved and left the Russian Federation as its legal successor. Further, when Ukraine undertook to forego its nukes, that was in express guarantee of Ukrainian sovereignty within the present borders, signed by the Russian Federation.

I, too, wish that Khruschev "with roaches in his head" did not signed over the Crimea to Ukraine, but on the other hand I'd rather have international law respected than another Sov country pop up.

Obviously, the New Ukraine has to deal with the fact that a single largest ethnic minority in their country is Russian speakers. And we have a large ethnic minority that is Spanish speakers. So? How does that impact the issues of national sovereignty?

The Russian Federation has ethnic minorities all over the place, by the way. Putin just opened the door for the dissolution of the RF if the separatist logic is to prevail.

When Ukraine gave up its nukes, the US alongside the Russian Federation took the responsibility of guaranteeing the territorial integrity of Ukraine.

The next stage was the signing on January 14, 1994 of the Trilateral Statement by the Presidents of Ukraine, Russia, and the United States under which Ukraine was to destroy all nuclear weapons on its territory, including strategic offensive weapons. Ukraine, Washington and Moscow reached an agreement in January that allowed for the dismantling of Ukraine's 176 Intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBMs) ahead of Kiev's formal ratification of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).[3][4] France and China provided unilateral security assurances in the form of diplomatic notes. The missiles—130 SS-18s and 46 SS-24s—carried about 1,800 nuclear warheads altogether.

On December 5, 1994, Ukraine acceded to the Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. On that same date, the US, Russia and United Kingdom provided security assurances to Ukraine, and the START I Treaty also entered into force.

There are plenty of full-blown Sovs with Ukrainian surnames, too. Mostly in the Ukrainian East and South.

Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances is an international treaty signed on February, 5, 1994, in Budapest by Ukraine, the United States of America, Russia, and the United Kingdom concerning the nuclear disarmament of Ukraine and its security relationship with the signatory countries. According to the memorandum, Russia, the USA, and the UK confirmed, in recognition of Ukraine becoming party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and in effect abandoning its nuclear arsenal to Russia, that they would:

- Respect Ukrainian independence and sovereignty within its existing borders.

- Refrain from the threat or use of force against Ukraine.

- Refrain from using economic pressure on Ukraine in order to influence its politics.

- Seek United Nations Security Council action if nuclear weapons are used against Ukraine.

- Refrain from the use of nuclear arms against Ukraine.

- Consult with one another if questions arise regarding these commitments.

Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances

It was, however, never ratified.

Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances was a international treaty signed on February, 5, 1994, in Budapest.The diplomatic document saw signatories make promises to each other as part of the denuclearization of former Soviet republics after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

It was signed by Bill Clinton, John Major, Boris Yeltsin and Leonid Kuchma – the then-rulers of the USA, UK, Russia and Ukraine.

The agreement promises to protest Ukraine's borders in return for Ukraine giving up its nuclear weapons.

It is not a formal treaty, but rather, a diplomatic document.

It was an unprecedented case in contemporary international life and international law.

Whether is it legally binding in complex.

'It is binding in international law, but that doesn't mean it has any means of enforcement,' says Barry Kellman is a professor of law and director of the International Weapons Control Center at DePaul University's College of Law told Radio Free Europe.

Thanks for the flag. This gives me a better understanding of the issue of Crimea, and what a pleasure to read the work of someone who actually knows how to write.

BTW, please clear this up for me. For the pronunciation of “Sevastopol” is the accent on the second syllable or on the third?

"He wasn't," she snapped. "Khrushchev had roaches in his head."

That could explain a few things.

Instead security assurances to Ukraine (Ukraine published the documents as guarantees given to Ukraine[5]) were given on 5 December 1994 at a formal ceremony in Budapest (known as the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances[6]), may be summarized as follows: Russia, the UK and the USA undertake to respect Ukraine's borders in accordance with the principles of the 1975 CSCE Final Act, to abstain from the use or threat of force against Ukraine, to support Ukraine where an attempt is made to place pressure on it by economic coercion, and to bring any incident of aggression by a nuclear power before the UN Security Council.

In other words, no guaranties and only the most tepid of assurances.

The Sink Emperor wasn't called "Slick Willy" only for his slimy sexual proclivities.

It would be nice if international law were to be respected but it doesn’t always happen. Crimea has been in Russia’s sphere of influence for centuries , and will continue to be for centuries more.

Sevastopol (/ˌsjivæˈstoʊpəlj/[1] or, more usually, /sɨˈvæstəpəl, -pɒl/[citation needed]; Ukrainian and Russian: Севасто́поль; Crimean Tatar: Aqyar; Greek: Σεβαστούπολη, Sevastoupoli)

In English traditional pronunciation it is SeVASTopol. However, the Russians say it SevastOPolj (with a soft L). The Greek original is SevastOOpoli or even SebastOOPoli, the Noble City.

The guarantee is still there, but due to the lack of ratification it is not enforceable by us.

Obviously Obama is not going to do anything. Putin wins the game of chicken easily, and I still think Putin is himself a coward.

The fact remains that for Russia (some abstract, non-existent “Russia”), to claim Crimea back the RF needs to renounce its succession from the USSR and go back to the law system of the Russian Empire. Which I would heartily welcome.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.