Posted on 04/25/2009 9:37:46 PM PDT by naturalman1975

Yesterday, Saturday, 26th April 2009, was ANZAC Day in Australia and New Zealand - the day that these nations remember their men and women who have made the ultimate sacrifice in time of war. It is the anniversary of the day in 1915 when troops of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps went ashore at Gallipoli, Turkey - the first time substantial bodies of troops from those two young nations (Australia 1901, New Zealand 1907) had gone into battle as soldiers of their nations, rather than purely and soley as troops of the British Empire (although they still retained that status).

It is the day our nations were baptised in blood and it is a sacred day.

This ANZAC Day saw approximately 3500 Australian soldiers, sailors, and airmen deployed on twelve overseas operations and to the protection of our own borders. Australian troops are currently operationally deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, and other areas of the Middle East, the Sudan, East Timor, and the Solomon Islands. Approximately 600 troops of the New Zealand Defence Force (Te Ope Kaatua o Aotearoa) are operationally deployed to various operational areas in the Middle East, South Pacfic, Asia, and the Pacific.

In some of these cases, these troops are serving in support of United States lead operations.

Over the week surrounding ANZAC Day, I intend to post a daily message in honour of these troops and those who came before them, highlighting some areas of ANZAC history. As an Australian, I know Australia's military history better than New Zealands, so I may not do theirs justice - but I invite any Kiwis here to add anything they wish to. To some extent, I especially hope to address some areas of operations that involved Americans - I understand my audience, but I think people here do respect the contributions of those of all nations who have fought for freedom, and sometimes died for it.

Courtesy of YouTube

Australian Defence Force engages Taliban in Afghanistan

Courtesy of Wikipedia

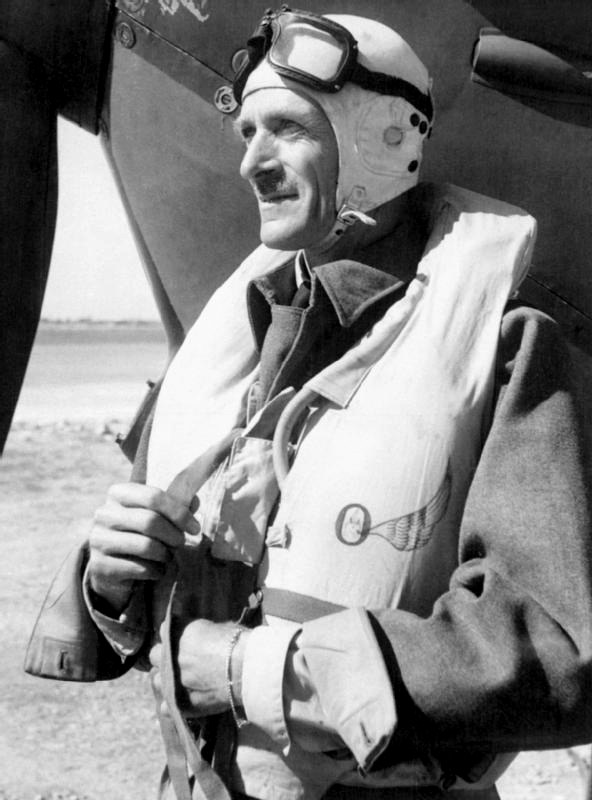

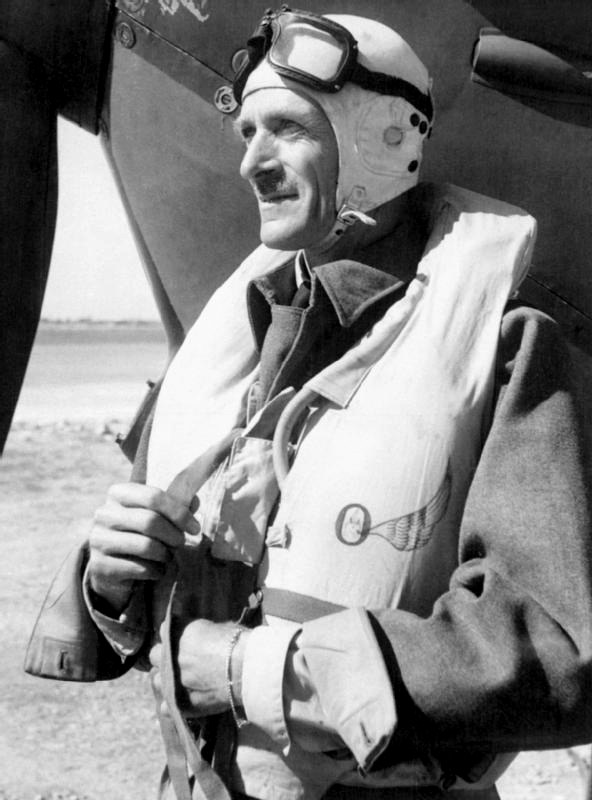

Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Rodney Park GCB, KBE, MC & Bar, DFC, RAF (15 June 1892 – 6 February 1975) was a First World War air ace and Second World War commander. During the Second World War, the Germans called him "the Defender of London".

Park was a New Zealand soldier, First World War air ace, and later senior commander in the Royal Air Force in the Second World War. He was in tactical command during two of the most significant air battles in the European theatre in the Second World War, the Battle of Britain and the Battle of Malta.

Park was born in Thames, New Zealand. He was the son of a Scottish geologist for a mining company. An undistinguished young man, but keen on guns and riding, Keith Park served in the cadets at school and joined the Army as a Territorial soldier in the New Zealand Field Artillery. In 1911, at age 19, he went to sea as a purser aboard collier and passenger steamships, earning the family nickname skipper.

When the First World War broke out, Park left the ships and joined his artillery battery. As a non-commissioned officer he participated in the landings at Gallipoli in April 1915, going ashore at Anzac Cove. In the trench warfare that followed Park distinguished himself and in July 1915 gained a commission as second lieutenant. He commanded an artillery battery during the August 1915 attack on Suvla Bay and endured more months of squalor in the trenches. At this time he took the unusual decision to transfer from the New Zealand Army to the British Army, joining the Royal Horse and Field Artillery.

Park was evacuated from Gallipoli in January 1916. The battle had left its mark on him both physically and mentally, though, in later life, he would remember it with nostalgia. He particularly admired the ANZAC commander, Sir William Birdwood, whose leadership style and attention to detail would be a model for Park in his later career.

After the hardship at Gallipoli, Park's battery was shipped to France to take part in the Battle of the Somme. Here he learned the value of aerial reconnaissance, noting the manner in which German aircraft were able to spot Allied artillery for counterbattery fire and getting an early taste of flight by being taken aloft to check his battery's camouflage. On 21 October 1916, Park was blown off his horse by a German shell. Wounded, he was evacuated to England and graded "unfit for active service," which technically meant he was unfit to ride a horse. After a brief spell recuperating and doing training duties at Woolwich Depot, he joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in December 1916.

In the RFC Park first learned to instruct and then learned to fly. After a spell as an instructor (March 1917 to the end of June) he was posted to France and managed a posting to join 48 Squadron, at La Bellevue (near Arras), on 7 July 1917. Within a week the squadron moved to Frontier Aerodrome just east of Dunkirk. Park flew the new Bristol Fighter (a two-seat biplane fighter and reconnaissance aircraft) and soon achieved successes against German fighters, earning, on 17 August, the Military Cross for shooting down one, two "out of control" and damaging a fourth enemy during one sortie. He was promoted to temporary captain on 11 September.

After a break from flying he returned to France as a major to command 48 Squadron. Here he showed his ability as a tough but fair commander, showing discipline, leadership and an understanding of the technical aspects of air warfare.

By the end of the war the strain of command had all but exhausted Park, but he had achieved much as a pilot and commander. He had earned a bar to his Military Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross and the French Croix de Guerre. His final tally of aircraft claims was five destroyed and 14 (and one shared) "out of control". (His 13th "Credit"—of 5 September 1917—was Lieutenant Franz Pernet of Jasta Boelcke (a stepson of General Erich Ludendorff) killed.) He was also shot down twice during this period.

After the Armistice he married the London socialite Dorothy "Dol" Parish.

Between the wars Park commanded RAF stations and was an instructor before becoming a staff officer to Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding in 1938.

Promoted to the rank of air vice marshal, Park took command of No. 11 Group RAF, responsible for the fighter defence of London and southeast England, in April 1940. He organized fighter patrols over France during the Dunkirk evacuation and in the Battle of Britain his command took the brunt of the Luftwaffe's air attacks. Flying his personalised Hawker Hurricane around his fighter airfields during the battle, Park gained a reputation as a shrewd tactician with an astute grasp of strategic issues and as a popular "hands-on" commander. However, he became embroiled in an acrimonious dispute with Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, commander of 12 Group. Leigh Mallory, already envious of Park for leading the key 11 Group while 12 Group was left to defend airfields, repeatedly failed to support Park. Park's subsequent prickliness of character during the Big Wing controversy contributed to his and Dowding's removal from command at the end of the battle. Park was to be bitter on this matter for the rest of his life. He was sent to Training Command

In January 1942 Park went to Egypt as Air Officer Commanding, where he built up the air defence of the Nile Delta. In July 1942 he returned to action, commanding the vital air defence of Malta. From there his squadrons participated in the North African and Sicilian campaigns.

In June 1944, he was considered by the Australian government to command the RAAF, because of rivalry between the nominal head, Chief of the Air Staff Air Vice Marshal George Jones and his deputy the operational head, Air Vice Marshal William Bostock, but General Douglas MacArthur said it was too late in the war to change. In February 1945 Park was appointed Allied Air Commander, South-East Asia, where he served until the end of the war.

On leaving the Royal Air Force he personally selected a Supermarine Spitfire to be donated to the Auckland War Memorial Museum. This aircraft is still on display today along with his service decorations and uniform.

He retired and was promoted to Air Chief Marshal on 20 December 1946 and returned to New Zealand, where he took up a number of civic roles and was elected to the Auckland City Council. He lived in New Zealand until his death on 6 February 1975, aged 82 years.

Flight Lieutenant William Ellis (Bill) Newton VC was an Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to a member of the British and Commonwealth forces. He was honoured for his actions as a bomber pilot in Papua New Guinea during March 1943 when, despite intense anti-aircraft fire, he pressed home a series of attacks on the Salamaua Isthmus, the last of which saw him forced to ditch his aircraft in the sea. Newton was still officially posted as missing when the award was made in October 1943. It later emerged that he had been taken captive by the Japanese, and executed by beheading on 29 March.

Raised in Melbourne, Newton excelled at sport, playing cricket at State level. He joined the militia in 1938, and enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force in February 1940. Described as having the dash of "an Errol Flynn or a Keith Miller", Newton initially served as a flying instructor in Australia before being posted to No. 22 Squadron in New Guinea, operating Boston light bombers. He was on his fifty-second mission when he was shot down and captured. Newton's was the only Victoria Cross awarded to an Australian airman in the South West Pacific theatre of World War II, and the only one earned by an Australian flying with an RAAF squadron.

Born in the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, Bill Newton was the son of dentist Charles Ellis Newton and his wife Minnie. He was educated at Melbourne Grammar School, where he completed his Intermediate Certificate. Considered at school to be a future leader in the community, Newton was also a talented all-round sportsman, playing Australian rules football, golf and water polo, as well as gaining selection in the Victorian Cricket Association Second XI.

Newton had been a sergeant in his cadet corps at school, and joined the militia on 28 November 1938. Employed in a silk warehouse when World War II broke out in September 1939, he resigned to enlist the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) on 5 February 1940. Newton underwent flying training at RAAF Laverton, and was commissioned as a Pilot Officer on 28 June. After completing his advanced training at RAAF Point Cook in September, he became a flight instructor, and was promoted to Flying Officer on 28 December. He served with No. 2 Service Flying Training School, Wagga, and No. 5 Service Flying Training School, Uranquinty. Newton was raised to Flight Lieutenant on 1 April 1942 and posted to No. 22 Squadron, based at Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea, the following month.

Flying a Douglas Boston twin-engined bomber, Newton made the first of his fifty-two operational sorties on 1 January 1943. During February he flew low-level missions through monsoons and hazardous mountain terrain, attacking Japanese forces ranged against Allied troops in the Morobe province. In early March he took part in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, one of the key engagements in the South West Pacific theatre, bombing and strafing Lae airfield to prevent its force of enemy fighters taking off to intercept Allied bombers attacking the Japanese fleet.

Newton gained a reputation for driving straight at his targets without evasive manoeuvre, and always leaving them in flames. This earned him the nickname "The Firebug".

On 16 March, Newton led a sortie on the Salamaua Isthmus in which his aircraft was hit repeatedly by Japanese anti-aircraft fire, damaging fuselage, wings, fuel tanks and undercarriage. In spite of this he continued his attack and dropped his bombs at low level on buildings, ammunition dumps and fuel stores, returning for a second pass at the target in order to strafe it with machine-gun fire. Newton managed to get his crippled machine back to base and, two days later, made a further attack on Salamaua with five other Bostons. As he bombed his designated target, Newton's aircraft was seen to burst into flames. Attempting to keep his aircraft aloft as long as possible to get his crew away from enemy lines, he was able to ditch the Boston in the sea approximately 1,000 yards (910 m) offshore.

The Boston's navigator, Sergeant Basil Eastwood, was killed in the landing but Newton and his wireless operator, Flight Sergeant John Lyon, survived and swam for shore. They were soon captured, however, by a Japanese patrol of No. 5 Special Naval Landing Force. The two airmen were taken back to Salamaua and interrogated until 20 March, before being moved to Lae where Lyon was bayoneted to death on the orders of Rear Admiral Fujita, the senior Japanese commander in the area.

Newton was later returned to Salamaua where, on 29 March 1943, he was beheaded with a Samurai sword by Sub-Lieutenant Komai, the naval officer who had captured him. Komai was killed in the Philippines soon after, and Fujita committed suicide at the end of the war.

It was initially believed that Newton had failed to escape from the Boston after it ditched into the sea, and he was posted as missing. The details of his capture and execution were only revealed later that year in a diary found on a Japanese soldier. Newton was not specifically named, but circumstantial evidence clearly identified him, as the diary entry recorded the beheading of an Australian Flight Lieutenant who had been shot down by anti-aircraft fire on 18 March while flying a Douglas aircraft. The Japanese observer described the prisoner as "composed" in the face of his impending execution, and "unshaken to the last".

General Headquarters South West Pacific Area, however, while releasing details of the execution on 5 October, initially refused to name Newton. Aside from the lack of absolute certainty, Air Vice Marshal Bill Bostock, Air Officer Commanding RAAF Command, contended that identification would change the impact of the news upon Newton's fellow No. 22 Squadron members "from the impersonal to the closely personal" and hence "seriously affect morale". News of the atrocity provoked shock in Australia. To alleviate anxiety among the families of other missing airmen, the Federal government announced on 12 October that the relatives of the slain man had been informed of his death.

Newton was awarded the Victoria Cross on 19 October 1943 for his actions on 16–18 March, becoming the only Australian airman to earn the decoration in the South West Pacific theatre of World War II, and the only one while flying with an RAAF squadron. The citation, which incorrectly implied that he was shot down on 17 March rather than 18 March, and as having failed to escape from his sinking aircraft, read:

The KING has been graciously pleased, on the advice of Australian Ministers, to confer the VICTORIA CROSS on the undermentioned officer in recognition of most conspicuous bravery: —

Flight Lieutenant William Ellis NEWTON (Aus. 748), Royal Australian Air Force, No. 22 (R.A.A.F.) Squadron (missing).

Flight Lieutenant Newton served with No. 22 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force, in New Guinea from May, 1942, to March, 1943, and completed 52 operational sorties.

Throughout, he displayed great courage and an iron determination to inflict the utmost damage on the enemy. His splendid offensive flying and fighting were attended with brilliant success. Disdaining evasive tactics when under the heaviest fire, he always went straight to his objectives. He carried out many daring machine-gun attacks on enemy positions involving low-flying over long distances in the face of continuous fire at point-blank range.

On three occasions, he dived through intense anti-aircraft fire to release his bombs on important targets on the Salamaua Isthmus. On one of these occasions, his starboard engine failed over the target, but he succeeded in flying back to an airfield 160 miles away. When leading an attack on an objective on 16th March, 1943, he dived through intense and accurate shell fire and his aircraft was hit repeatedly. Nevertheless, he held to his course and bombed his target from a low level. The attack resulted in the destruction of many buildings and dumps, including two 40,000-gallon fuel installations. Although his aircraft was crippled, with fuselage and wing sections torn, petrol tanks pierced, main-planes and engines seriously damaged, and one of the main tyres flat, Flight Lieutenant Newton managed to fly it back to base and make a successful landing.

Despite this harassing experience, he returned next day to the same locality. His target, this time a single building, was even more difficult but he again attacked with his usual courage and resolution, flying a steady course through a barrage of fire. He scored a hit on the building but at the same moment his aircraft burst into flames.

Flight Lieutenant Newton maintained control and calmly turned his aircraft away and flew along the shore. He saw it as his duty to keep the aircraft in the air as long as he could so as to take his crew as far away as possible from the enemy's positions. With great skill, he brought his blazing aircraft down on the water. Two members of the crew were able to extricate themselves and were seen swimming to the shore, but the gallant pilot is missing. According to other air crews who witnessed the occurrence, his escape-hatch was not opened and his dinghy was not inflated. Without regard to his own safety, he had done all that man could do to prevent his crew from falling into enemy hands.

Flight Lieutenant Newton's many examples of conspicuous bravery have rarely been equalled and will serve as a shining inspiration to all who follow him.

The second battle of Villers-Bretonneux, 27-27 April 1918, took place during General Ludendorff’s great spring offensive of 1918. His first major offensive, the second battle of the Somme, had come close to creating a gap between the British and French lines. It had also reached to within ten miles of Amiens, before being stopped in the first battle of Villers-Bretonneux. After the failure of the Somme offensive, Ludendorff had turned north, launching a second offensive against the British in Flanders.

The second battle of Villers-Bretonneux came during the period of the battle of Lys, but was launched further south, in an attempt to break the British lines in front of Amiens (held by the 8th Division).

The German attack was supported by 13 of their A7V tanks, making it one of the biggest attacks launched by the German built tank. It would also see the first tank-vs-tank battle, a confrontation between three A7Vs and three British Mk IVs.

The German attack was preceded by a short artillery bombardment, with a mix of mustard gas and high explosive shells. The 8th Division was overwhelmed. A three mile wide gap was opened in the British lines, and Villers-Bretonneux fell to the Germans. There was a serious danger that the Germans might break through to Amiens.

General Rawlinson responded by launched an immediate counterattack. This would be a night attack, to be launched by two Australian brigades – the 13th (Brigadier Elliot) and 15th (Brigadier Glasgow). The attack, on the night of 24-25 April, was a total success. By dawn the main German line had been forced back, and the troops in Villers-Bretonneux cut off. By the end of the day the village was back in Allied hands. The Australians suffered 1,455 casualties during the battle.

The Australian War Memorial in France is located in Villers-Bretonneux and in front of it lie the graves of over 770 Australian soldiers, as well as those of other Commonwealth soldiers involved in the campaign. The school in Villers-Bretonneux was rebuilt using donations from school children of Victoria, Australia (many of whom had relatives perish in the town's liberation), and, to this day, above every blackboard is the inscription

"N'oublions jamais l'Australie"

Never Forget the Australians

I attended a dawn ANZAC ceremony here in Canada on April 25. Nice crowd I thought which was swelled by good weather overall and visiting delegation of Australian senators.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.