Here are three drawings (out of hundreds) by a young artist who uses only triangles to form pictures.

"Salaryman"

~ or ~ "Tyu"

~ or ~

"Close"

Posted on 06/12/2005 6:08:39 PM PDT by vannrox

One of the enduring myths about the so called modern "art" is the need (?) to understand it. According to its apologists without understanding there is no real or proper appreciation of the painting/sculpture that one is looking at. In other words a process that naturally begins and ends at the heart must begin in our brain. That means we have already made a wrong start. I remember a quote from Renoir, a painter who is not a favourite of mine but who, nevertheless, hit the nail right on its head when he said: "... art is about emotion, if art needs to be explained it is no longer art." With these words in mind we may proceed to unravel this web of lies that pretends to create something out of nothing.

The innate desire of the European soul for an honest, truthful representation of Nature in all its aspects has resulted in what we call Western art; a process whose origins can be traced back to the XV century in Italy and that reached its zenith in the late XIX century with the striking realism developed by masters like Meissonier, Leibl, Bonnat and Repin. Like all genuine manifestations of an unpolluted culture, it does not need any explanation to make it understandable. It is a feeling born of a deep yearning for beauty and harmony. A typical Flemish or Dutch still-life of the XVII century could, and can be, fully appreciated and enjoyed without any need of obtuse explanations about its "psychological meaning" or the "state of mind of the artist"; misleading expressions that have served to confuse people, pervert our appreciation of art and, last but not least, to justify the production of hundreds of books, some of them fairly expensive, which are not worth the paper they are printed on.

Some could, or would, say that this is not exactly true; that many Dutch still-lives, for example, carry a subtle but clear religious message expressed through the use of certain emblematic flowers or objects. The purpose of these subtle allegories was to remind the viewer the basic tenets of the Calvinist faith. This kind of painting could only be fully appreciated by educated connoisseurs who were familiar with emblematic iconography. Whereas all this is very true, it does not detract from the fact that the primeval virtue of a Dutch still life was its intrinsic beauty (as it is still today). Those who try to use the case of the allegorical Dutch still-life as an example of sophisticated art in need of elucidation miss completely the point when they forget that this genre (still-life) was already a firmly established and thoroughly popular Netherlandish form of art. The fact that many wealthy and, usually, highly educated Dutch art collectors commissioned large and sumptuous still-lives, devoid of any religious or moral messages, makes very clear that the main reason behind their commissions was an aesthetic one.

Some could also say that most of European paintings that represent historical or mythological episodes fall into the same category; that is, they need to be "explained" since most of its narrative content remains a mystery to the average viewer who does not possess an encyclopedic knowledge. That is also wrong since the main reason that makes us to stop and stand in front of a painting is its beauty; expressed in its skilful composition, sound draughtsmanship and beautiful colouring. We do not need to know Greek mythology to enjoy Frederick Leighton's Daedalus and Icarus (Buscot Park, Oxfordshire) or Perseus and Andromeda (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool), neither do we need to know who was Napoleon to admire his magnificent equestrian portrait by David known as Napoleon crossing the Alps (Louvre). It is irrelevant if we know, or if we do not, who was St. Matthew when we look at Carlo Dolci's beautiful painting St. Matthew writing the Gospel (Paul Getty Museum). Needless to say the same principle applies to sculpture. One does not have to be a Catholic to be moved by Bernini's masterpiece The Ecstasy of St. Teresa (Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome), neither an expert in Greek mythology to admire his superb Apollo and Daphne (Galleria Borghese). We could go on indefinitely.

European traditional painting and sculpture have this attribute in common: They appeal to our senses because they are a mirror of Nature; therefore we can easily identify ourselves with the persons or objects portrayed, because they belong to the same three-dimensional world we inhabit. It is their formal beauty, conjured by the magical brush, or chisel, of the artist, that attracts us to them. The degree of knowledge of History, Classical mythology, Christian theology and symbolism that we may, have does not have any relevance in the actual enjoyment of the work of art in itself. It can only enhance our critical appreciation of it as a representation of a certain historical or mythological episode, but it would never replace or influence our aesthetic judgment. We would like it, or not, purely on emotional terms; and to do that we do not need any explanations or theories. There is nothing to "understand" but plenty to feel.

Because of its intrinsic ugliness and lack of purpose according to our traditional concept of beauty and decorum, the phenomenon known as modern art needs an intellectual structure or theory to support something that, left to itself, would disappear among derisory laughter. Hence this need "to understand" it. Once we have been foolish enough to accept the validity of such nonsense we are lending ourselves open to an unbearable barrage of words that have precisely the same purpose of the artillery shells employed in a real one: that is to leave you in a state of shock (if they did not kill you before). This display of pretentious intellectualism has a purpose: to convince you that you are ignorant and unable to "understand" modern art; therefore you need tuition. This will take the shape of flashy exhibition catalogues or "serious" art books that are a combination of Freudian nonsense and wishful thinking. Since modern art is about anything you can imagine except art (in the classical sense), it can be anything; in fact is anything you may want it to be. If we carry out a survey among 500 people that have been shown an abstract painting and asked them their opinion about the subject of it, most probably we would end up with 500 different answers ranging from: "It is my mother's cat ..." to "it is an expression of the artist's anger against the destruction of the rainforest ..." More likely, most of them would agree that "it is a beautiful painting" because there is nothing as embarrassing as to confess our ignorance; such is the effect of the modernist brainwashing techniques. Very few would have the courage to say: "it is rubbish" following the time-honoured practice of calling things by their name.

Since modern art is no more than "a high sounding nothing", to use Metternich's famous expression, this nothing needs a perpetual choir of apologists and elucidators, the noisier the better, to ensure that the crowds of pretentious fools that visit modern art exhibitions, and buy the ridiculously expensive catalogues, keep doing so. On the other hand it must be said that this whole farcical structure rests on solid foundations: the unbearable stupidity of the snobbish Western middle-class nitwit that would die before admitting he does not understand a word of what is said in that useless art book he, or she, has just purchased and that would end on the coffee table, to the sheer delight of like-minded visitors (isn't it magnificent...?). Once this people are forced into a tight corner, in a metaphorical sense of course, they either fell apart or start getting angry at you. The fact is: these people are living in a state of perpetual contradiction. Let's begin for the expression modern art which is an oxymoron, because art (according to The Concise Oxford Dictionary) means: "Skill, especially human skill as opposed to nature; skilful execution as an object in itself; skill applied to imitation & design, as in painting etc." The only skill exercised by the modern "masters" is the one applied to marketing and public relations, because without the support of a huge network of subservient art critics, cynical art dealers, powerful museums and institutions that have great interest in its promotion, this glorified high sounding nothing would have disappeared long time ago destroyed by its own sick nature.

Here are three drawings (out of hundreds) by a young artist who uses only triangles to form pictures.

"Salaryman"

~ or ~ "Tyu"

~ or ~

"Close"

I stand corrected, ma'am.

I remembered the story and the fog of time caused me to assume that a spattered dropcloth was naturally a Pollack.

Do you also remember when, one year, at the Piedmont Arts Festival, an artist created a sculpture entirely of sod that was discovered by the grounds crew and utilized for its natural purpose?

Like everyone else, including the maintenance guys, I assumed it was part of the construction debris. It was only after the fit hit the Shan that I thought back and said, "So THAT's what that was! I wondered why I didn't see any painting going on."

Funny, because my mom used to be pretty heavily involved in the Piedmont Arts Festival.

Art Ping.

Let Sam Cree or I know if you want on or off this list.

I have no time to read this article at the moment, but I will later and duly respond.

Thanks.

|

|

| Art | Garbage |

Yes, one can always "appreciate" art just for its visual appeal, be it Matisse or Botticelli. But that may be a more superficial level. One can gain a deeper intellectual, visual and emotional understanding if one digs a bit deeper.

Let's look at two prime examples: Botticelli's Primavera from 1482 and Picasso's Guernica from 1937.

Right off, one can tell that the subjects are different and that there are different emotional impacts. So, if you don't know anything about these works, what can you learn just by looking? If you know Italian, you can tell that Botticelli's work is about spring. There is a pretty girl in the middle and something weird happening to a woman on the right.

Many art historians have in fact argued (very eruditely) about what this work means and who these people are. The explanation I like is that this is not only about spring but about three different stages of love. The West Wind (Zephyr) comes in from the right and represents March; Mars, symbol of May, raises his object on the left and stops the sweep of Spring. On that right, Zephyr has also abducted Chloris and, after the “seduction” (or rape), she becomes Flora the Roman goddess of flowers. This represents sexual love. Off center to the left, the three Graces (showing all sides important to men’s eyes, underneath very skimpy drapery) represent platonic love, with several symbolic interpretations to the height of their hands. The lady in the middle is Venus and looks uncannily like a woman who was engaged to a Medici (THE rich family in Florence, where Botticelli was painting). Mars looks a great deal like a young Medici of the time. One interpretation is that this is a wedding painting for them, with symbols of various kinds of love. Thus the central lady is a rather virtuous Venus (since she is clothed) who will be married to Mars. She represents marital love. There is even more symbolism: from the oranges to the designs on her drapery, but they can all support this interpretation.

Did you get all that by looking at the painting? I sure didn’t. I only know it because I’ve taught it a zillion times.

Lastly, is Botticelli perfectly “realistic?” No. No drapery falls like that. He has changed things, perfected his forms to an ideal. His use of line is incredible: weaving and winding and flowing in lovely (but totally unrealistic) ways. There’s nothing wrong with that; he is to be applauded by not being constricted to “realism” from the real world and for pushing his own style to “say” something else. (One could also dive really deeply into Neoplatonic philosophy, to which Botticelli was devoted, and make those connections with this painting, but I will spare you….)

And what is going on in Picasso’s work? Can you decipher anything? You may be able to decipher here more than you think, and more than you can in the Botticelli. What does the bull represent? (The bull may represent Spain, or even Franco, the soon-to-be dictator of Spain.) What is going on with the woman and child in the left? If you are saying the woman is upset because her child is dead, you are right. This also connects to many images of Mary with the Christ Child in her lap, as child and as adult. I also think that the spike in this woman’s mouth, and in the horse, as well as the distortions of their heads, can convey physical and emotional pain even more strongly than in any representational image.

What’s happened to the soldier lying in the middle? Yes, he is dead; but note the flower in his hand; this give a sense of hope as well as fragility. What is that light in the middle? Could it also be seen as a sun and as an eye? Definitely. The woman on the right with the torch is coming in to light up the scene; note the horse has a newsprint texture. This painting (which is HUGE) was done after Franco called in the Germans to help with the Spanish Civil War. This was the first use of saturation bombing, where more civilians were killed than military personel, and a town with no military significance was bombed almost out of existence. This kind of bombing turned out to be a main event in WWII. This is a black and white painting, although one of my students (who saw it in person in Madrid’s Prado) could have sworn there was blood red in it! (This internet image is a bit too blue…sorry about that.)

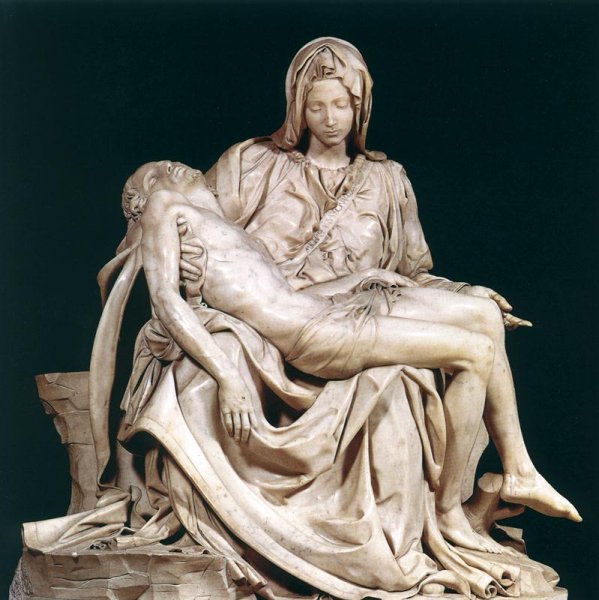

Other images of Mother and Child and Pieta images.

.jpg)

Michelangelo: two Pietas, one early, one late; Raphael Alba Madonna

Pieta, by the way, is a fancy word for pity and was a subject (not in the Bible) that was devised by artists to bring the most compassion for Christ after his death, lying in Mary’s lap.

Now, be honest….which piece really moves you, affects you and reflects the events of the 20th century? When Einstein came up with his theories of relativity, time, life and art changed. More about this later on. But the really cool thing about early modern art is that certain symbols (like that lightbulb in Picasso) can represent many other things as well.

Also, I wish the author, Claudio Lombardo, would use more discrimination in the labeling of art. "Modern" is not just art of the whole twentieth century. "Contemporary art," that art after 1950 or 1960, is probably more relevant to the disgust the viewer feels.

That image is the Broken Kilometer by de Maria, 1970s. This is installed in NYC and is parts of a kilometer broken up. Not a lot of depth here; even I don’t think this is a great work of art. This is contemporary site work and is, in retrospect, rather gimmicky and empty. I don’t have a problem being critical with this kind of work, and I think that Lombardo means this kind of work when he attacks “modern” art. But more discrimination of terminology would be appreciated.

Unfortunately, I think this writer has such an axe to grind that he has closed himself off to all other possibilities.

Great story. Thanks for the clarification. Where was this, where you were working?

Thanks for the penis picture.

It contains the Federal District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, the U.S. Attorney's office, the magistrates and bankruptcy judges, as well as a lot of other federal offices that are on other elevator banks so I have no idea what they are. I was a young law clerk fresh out of law school at the time, clerking for one of the district judges.

I'm not sure that's Mars in the Primavera. I'm a classicist, not an art historian, but the male figure on the far left does not have the traditional attributes of Mars (spear & shield, helmet, etc.) and he does have those of Hermes - the staff, the boots (are wings visible in the original?) and the fact that he is a youth rather than a mature man. Hermes DID carry a sword (he slew a giant with one, and gave one to Heracles and another to Perseus) so that's not necessarily indicative of Mars.

As you know, Picasso refused to allow his work to be exhibited in Spain while Franco was alive so Guernica hung in the Museum of Modern Art in NYC for years. I visited the museum for the first time in the 70's while in college and Guernica was hanging right out in the open with no barriers in front of it. I stood in front of it and was transfixed. For reasons I still can't explain I reached out to touch it. Just before my hand touched the canvas my arm was wrenched behind my back and two large, angry security guards I hadn't even seen hustled me out with a few choice expletives.

I was shook up for a long time. I obviously didn't mean any vandalism, it's just the painting had such an effect on me that I wasn't even thinking straight. I just wanted to touch it since it had touched me. Crazy, I know.

Last year we went to Madrid and I saw it again at the Reina Sofia museum. I think they saw me coming and doubled the guards. Anyway, I made sure to keep my hands in my pockets.

No work of art has ever affected me the way Guernica has.

I understand your feelings perfectly. Fortunately, my passion is for miniature painting, manuscript illumination and calligraphy, things that generally fit underneath an overcoat, so thus far I've been blessed to make it out of the museum before the guards got wise to me. So far I've been captivated BY many pieces, just not because of them...

The Voynich Manuscript is my current obsession...I might have to spend some time in Yale for that one!!!

LOL! I won't tell anyone if you cut me in on the proceeds!

I guess you are so famous, they are still looking out for you. Pretty cool.

I like that very much, thanks. I would point out, also, that all representational art is abstract to some degree. Every artis alters reality a little with his own individuality.

artis = artist

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.