Posted on 11/01/2017 10:48:34 AM PDT by Red Badger

The Patriots legend thinks he can play until he's 45 without sacrificing body, mind or integrity. But his future is not just in his hands.

t happened all at once, the way it happens to boxers. He had been baited into throwing a pass to the wrong man, and suddenly he stood exposed, with not only the play but nature itself turning against him. His teammates seemed to have disappeared; he was the last man in position to stop the wrong man from running all the way down the field and turning the game into a rout. He tried his best, as he always does, but he was alone against a younger, faster opponent, and when he dove, he missed by a foot rather than by an inch and appeared simply to fall down, in pieces. Even those who root against him might then have pitied him, because it was one of those moments when the essence of sport is revealed to be cruelly and coldly biological: Tom Brady, in the course of throwing a pick-six to Robert Alford of the Falcons in the second quarter of Super Bowl LI, had grown old.

Later, in the fourth quarter, Brady threw another pass over the middle to Alford. It was worse than the pick-six. Brady wasn't tricked; he was forcing the ball into traffic with the game on the line. This time, though, Alford didn't catch it. This time the ball caromed off his fingertips, still in play. It went up, came down, and Brady's intended receiver, Julian Edelman, leaped for it. He grabbed at it, but then so did gravity, and the ball fell toward the ground. But it didn't land on the ground. It landed on a trivet of Alford's splayed legs and Ricardo Allen's outstretched arms, and Edelman got his hands under it, in one of those moments when the essence of sport is revealed to be cosmic. By the measure of a vibrating inch, Tom Brady had overturned the verdict of time.

The oldest story in sports is not an athlete dying young. The oldest story in sports is an athlete getting old and playing past his prime, somehow hoping to avoid the inevitable. In September, Tom Brady released a book titled The TB12 Method: How to Achieve a Lifetime of Peak Performance, in which he attempts to rewrite the oldest story in sports. It is a brief against the inevitable, irresistible not because it supplies its readers with their own blueprint for beating the clock or because it provides access to the teachings of Brady's fitness adviser and business partner Alex Guerrero, but rather because Brady is living his method, and we don't know how his story ends.

Of course, we know how he wants it to end. In an interview with ESPN the day after the Patriots played the Falcons in a mid-October Super Bowl rematch, he says, "I want to play for a long time," as if he were at the start of his career rather than near the end. Indeed, the 18-year veteran said this year that he wants to play until he's 45. He wants to win a couple of more Super Bowls so his already unprecedented career is impossible to replicate. But his on-the-field ambitions might be a mere prelude to what he wants to achieve off the field, because The TB12 Method captures a man attempting to transform himself from a transcendent figure in sports to a transcendent figure in the culture.

Brady declares that he is "on a mission" and wants to "inspire a movement." That his movement is about something he calls "pliability" -- muscles trained to become "long, soft and primed" instead of "short, dense and stiff" -- is less telling than the moral case he makes for it. "Pliability is not just for elite athletes," he writes. "It's for anyone who wants to live a vital life for as long as possible." The Method is not of the locker room. Instead, it reflects the values of a global elite for which human longevity is human destiny, and of which Brady and his wife, Gisele Bundchen, are members in good standing.

There is just one catch to all this: To transcend football, Brady has to keep playing it. He has made himself a test case -- the test case -- for the ideas that form the foundation of TB12, his brand. "If you want proof that pliability and the TB12 Method works, I'm it," he writes. He doesn't just want to play until he's 45; he has to play until he's 45, or else he's not Tom Brady, architect of the impossible. Up against aging, injury and, possibly, the inscrutable long-range plans of his future Hall of Fame coach, Bill Belichick, Brady is playing a dangerous game within a dangerous game, and before he transcends football, he has to manage a feat almost as rare and unlikely: He has to survive it, with his body, his brain and his dignity intact.

On the Week 7 night when the Patriots and Falcons meet, New England enters the game at 4-2, in a 2017 season distinguished by its rate of attrition across the NFL, with elite player after elite player finding talent no protection from injury. Brady himself has acknowledged how often he's been hit as the season has worn on; he is said to be playing with an aching left shoulder, and when, early in the game, he moves out of the pocket and throws deep to a receiver, the pass finds its fluttering way, once again, into the hands of Robert Alford.

But then Brady gets a reprieve. As he let go of the ill-fated ball, he was hit hard and high, and, in the context of the 2017 season, yet again, by the Falcons' Adrian Clayborn. Clayborn is called for roughing the passer. Two plays later, Brady proves what every coach in the NFL already knows -- that he is a man who makes the most of second chances -- and tosses a touchdown pass to Brandin Cooks. The rout is on, with a pass thrown to Alford once again emblematic of the smiling face of fortune in Brady's career, except for this: He won a reprieve from an errant throw.

He did not win a reprieve from another hard shot to his head.

Take a look at him, at the Boston convention center, back in June. He is sharing a stage with two friends, Edelman and Tony Robbins, at one of Robbins' motivational extravaganzas. It is four months after Brady's fifth Super Bowl win, a day after the conclusion of the Patriots' minicamp, and he looks as relaxed as it is possible for him to look, his crisp denim shirt open over his clean white tee. When Robbins, smiling toothily in his headset, leads the crowd in rhythmic clapping, Brady gamely claps along. He is wearing his own headset, smiling his own toothy smile, and he appears for all the world to be an aging athlete doing what aging athletes have always done -- trying to find a way off the field by turning himself into a salesman.

Now take another look, keeping something very important in mind. He is Tom Freaking Brady, and so he is no more a standard-issue jock-turned-pitchman than he is a standard-issue NFL quarterback. Sure, he has something to sell, The TB12 Method and all its associated paraphernalia, from a $250 resistance band kit to a $200 cookbook. But he is not just hawking his wares; he is trying to start a movement. And so Robbins and Edelman are on hand not simply as friends, or even as comrades in arms. Robbins is a mentor, a glimpse of what Brady wants to become. Edelman is a disciple, an initiate into the mysteries of the TB12 Method. And the three men, seated onstage and rhythmically clapping, represent a tableau of belief, even when Robbins asks Brady about the minicamp.

"I walked off the field at practice and thought, 'I am the worst quarterback in the NFL,'" Brady says. "'How could I have possibly made those throws? How could I be so dumb to do that?'" He smiles impeccably. "If it's not perfect for me, I lose sleep."

It is hard to believe him when he talks like this. But he makes it hard to disbelieve him, because there is no way to explain his career without resorting to the inexplicable, and because he so clearly believes the unbelievable to the bottom of his soul. No matter what he happens to say, he means every word. He tells Robbins' audience the story of how he came to the Patriots as the 199th player in the 2000 NFL draft, with no one but him believing he had a chance to replace Drew Bledsoe as the starting quarterback. It is not just a story he has told many times before; it is the only story he has ever told, yet the audience is rapt because the people know there's a miracle at the end.

So take one more look at him as he tells of how his belief in himself was tested by struggle and then hardened into an implacable will, and of how that will now finds its perfect expression in the creation of the TB12 Method. It is one month after Bundchen told the world her husband has a history of undiagnosed concussions, including one he suffered last season. When Robbins asks Brady why he created TB12, he answers that he has been motivated by watching his idols fall. "Joe Montana had to retire because his body didn't hold up," he says. "Steve Young had to retire because he kept getting head injuries." Brady seems to imply that he can somehow avoid their fates by rigorous practice of the TB12 Method. And now in his book, he states outright that the responsibility for injury rests in part with the injured. "When athletes get injured, they shouldn't blame their sport -- or their age," he writes. "Injuries happen when our bodies are unable to absorb or disperse the amount of force placed on them."

He is challenging himself to accomplish feats unprecedented and miracles untold, and he is defending the game of football with the determination of a man defending his own legacy. His message is unmistakable: Football helps those who help themselves.

"There's always this baseline balance for me to find before every game," Brady says in the interview after the Falcons game. "Really, our goal with the book that I wrote was to describe all of those things. ... I've been doing it for so long it's not hard for me to understand. It's very simple, and it's probably more frustrating that more people don't just understand it."

The TB12 Method is Brady's first real book, but there is little surprise in the fact that it doesn't take the form of a memoir, an autobiography or a tell-all -- that it isn't even really about Brady. Never in the business of self-revelation, he reveals nothing in his book except that he is very much in the business of Tom Brady. Still, The TB12 Method is an exercise in unintentional self-disclosure.

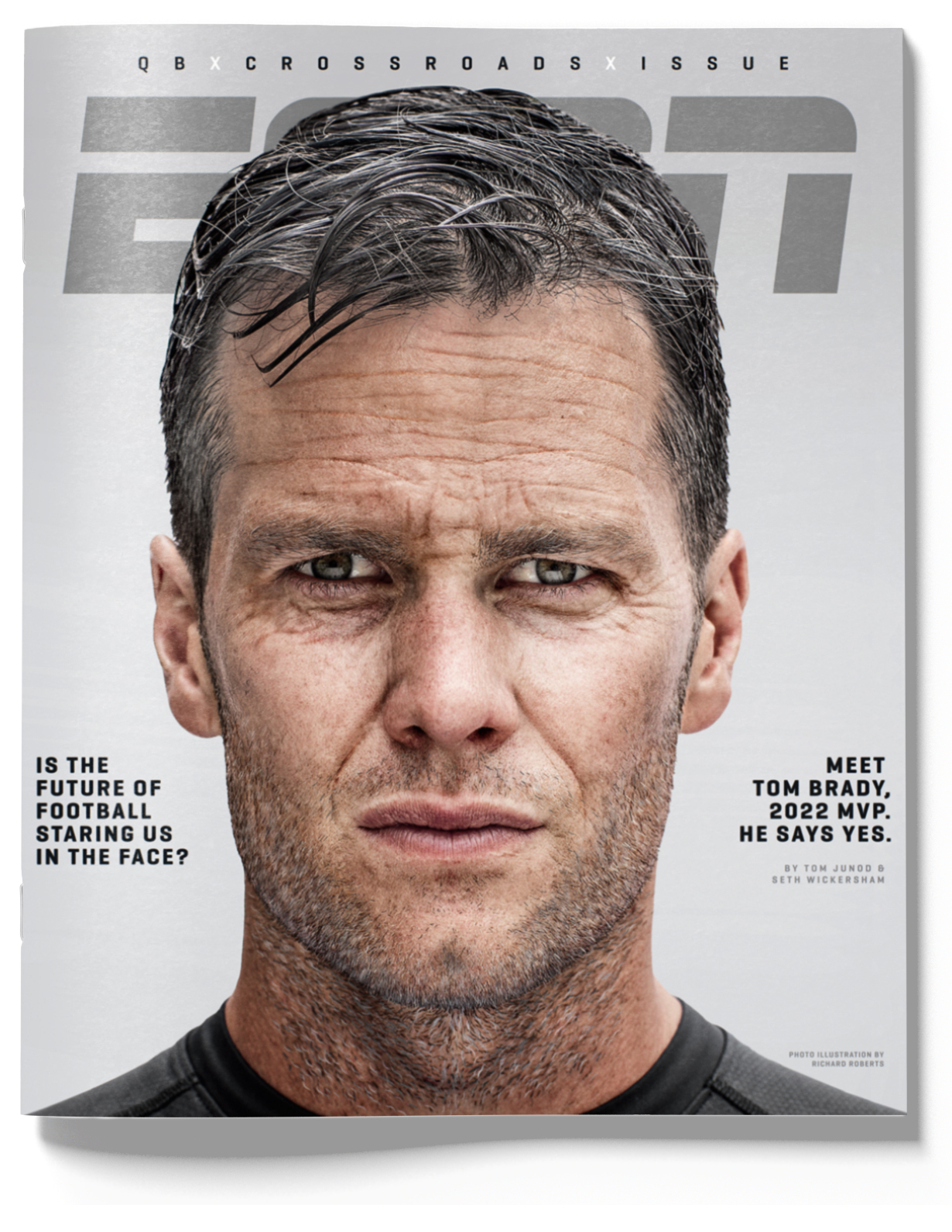

The man who gazes at us from the book's cover is a fair-skinned Californian, who after spending the better part of his life in the elements has somehow acquired nary a line or wrinkle, not a scar nor even, for that matter, a freckle. It is not so much that he looks young as that he refuses to look old. When his wife mentioned his concussions, she did so once and never again, and Brady has batted away questions about long-term neurological effects as "none of your business." The word "concussion" never appears in The TB12 Method. The phrase "brain injuries" does, but only when Brady is talking about techniques to "get ahead and stay ahead" of them, "especially in the off season." He answers questions about concussions by saying that his body is none of your business even as he begins to build a business around his body.

It has become customary to think of Brady as an athlete without limits, one who overturns expectation by refusing to concede an inch to anyone else's idea of the inevitable. But The TB12 Method offers a portrait of a ferociously limited human being, albeit the world's "most hydrated" one. Every day, he wakes up at 6 in the morning and immediately drinks 20 ounces of purified water, augmented with TB12 electrolytes, which, as he tells us, contain the "72 trace minerals" generally lost in perspiration. As a result, he says, he is so well-hydrated that "even with adequate exposure to the sun, I won't get sunburned," and he presumes that the muscles under his skin look like "beautiful tenderloins" instead of "shriveled jerky." He trains about four hours a day, and on most days, he "does pliability" with Guerrero, who, with hands capable of generating "50 newtons of force in a single finger" -- about 11 pounds -- applies "targeted pressure" to Brady's muscles. "On the rare occasions when I don't have the benefit of working with Alex," he either does "partner-pliability" or goes solo with a jar of coconut oil he applies himself and a TB12 "vibrating sphere." He eats abstemiously, with few portion sizes bigger than the palm of his hand, but also with a purpose, to maintain the "alkalinity" of his body. And he sleeps in the same determinedly therapeutic fashion, repairing to bed at 9 each night in a room uncontaminated by either technology or pet dander. He keeps a glass of water by his bedside and sleeps, famously, in TB12 "bioceramic recovery wear," which is also for sale from TB12 and which Brady also considers part of a "movement" -- the "tech-enabled apparel and sleepwear" movement.

Last year, he writes, he was so pleased with how he was throwing at a workout that "I remember thinking, 'My ability to sustain my peak performance over the past 10 years is almost unbelievable to me.'" With his "oxygen-rich blood" and his muscles "firing at 100 percent," he can now afford to say "I rarely get fatigued, I never get headaches and I never cramp." He all but pronounces himself invulnerable. He is not one of them, the irreparably damaged players we've come to pity even as we root them on. "I can recover from Sunday's game significantly faster than players who may be 10 or 15 years younger than me," he writes. But the stakes are even larger -- and the odds even longer -- than that, because Brady seems to be asking his readers to acknowledge not simply that he can recover but that he is unscathed, as if he were not playing in Sunday's games at all. "In fact, two years ago, I took a hit on my knee during a practice, requiring an MRI. The doctors who read the MRI joked afterward that my knee looked so healthy, they seriously doubted I played professional football."

Brady writes, "sustained peak performance isn't about luck" and claims that "much of the success I've been lucky enough to have in my career I owe to a lifelong 'will-over-skill' mindset." However, if Alford had caught the ball Brady threw to him instead of Edelman, or if the ball had followed its natural course and fallen to the turf instead of being held up by a thicket of arms and legs -- or if Pete Carroll had just handed the ball to Marshawn Lynch in Super Bowl XLIX -- we might be having an entirely different conversation about Tom Brady. He wouldn't be an immortal, and instead of talking about the efficacy of the TB12 Method in prolonging prime performance, we'd be shaking our heads about another NFL great reduced to chasing his own ghost. Brady didn't only get good against Seattle and Atlanta, he also got lucky.

Luck has not always gone his way. David Tyree ended Brady's dream of an undefeated 2007 season when he caught Eli Manning's desperate heave against his helmet, a catch at least as improbable as Edelman's. And at the start of 2008, Brady tore two ligaments in his left knee, an injury so severe there were doubts about his ability to recover. When he suffered complications from surgery, he hired Guerrero, with whom he had worked in the past, to find a better way. Now Brady credits Guerrero's "genius." He hugs him when he sees him and calls him "Alejandro." He overlooked issues in Guerrero's past -- Guerrero paid a judgment to the Federal Trade Commission to settle charges that he claimed dietary supplements could help cure cancer -- and went into business with him. He also brought teammates into his TB12 fold, mostly converting a circle of players that includes Danny Amendola, Dont'a Hightower, Rob Gronkowski and, of course, Edelman.

To what extent does Brady now think he controls his fate? "The moment another player's helmet makes contact with my body, my muscles are pliable enough to absorb what's happening instantly," he writes. "My brain is thinking only lengthen and soften and disperse before my body absorbs and disperses the impact evenly and I hit the ground." Or, more simply, as he puts it in the interview, "I know my focus on pliability has helped me avoid so many injuries and bounce back so quickly from hits."

Yet he remains an NFL player, and for any NFL player, the cruel whims of the game are not restricted to what happens on the field, especially when he's a New England Patriot and plays for a man with a formidable method of his own.

Bill Belichick is the coldest decision maker the game has ever known. He is a virtuoso strategist, but the essence of the Belichick Method is not only about plays but also about personnel, and knowing the earliest possible moment to let go of players who make the mistake of thinking they're indispensable. For the better part of two decades, Brady has stood as the exemplar of the Belichick Method, the coldest quarterback for the coldest coach. But he has also stood as its test, a question that one day Belichick would have to answer, the ultimate inevitability of his and Brady's careers.

Belichick appeared to have come up with his answer in 2014, when, in Brady's own words, "the youth had worn off" and the quarterback was still trying to adjust his game after five years of postseason struggle. Smart defensive coaches had started challenging him, clogging the middle of the field in order to force him to throw outside. In 2013, Brady's yards per attempt had fallen to 6.92, his lowest since 2006, and he completed only 17 of 68 throws beyond 20 yards. "We gotta be able to throw downfield," Belichick said, according to people on his staff, and though Brady, working with Guerrero, was already starting to talk about playing into his 40s -- prompting eye rolls from some Patriots staffers -- that wasn't the question that consumed New England personnel evaluators. The question was whether his skills were in irrevocable decline, and in the 2014 draft, Belichick seemed to come up with an answer by drafting Jimmy Garoppolo in the second round, the first signal that he was personally invested in a future that did not include Tom Brady and that the Belichick Method would never give way to mere sentiment.

The Chiefs drubbed the Patriots on Monday night early in the 2014 season, and Brady played so poorly -- so creakily -- that talk turned to whether he was, at long last, finished. A few days later, Belichick asked running backs coach Ivan Fears to speak to the team. Fears spoke about the importance of attitude, then turned to Brady and, with the entire team looking on, said, "Your body language reeks of fear."

In response, Brady did what Brady does: He willed himself to get better. He says he "doesn't remember" Fears saying that to him, but he will always remember the necessity, at that moment, for mental toughness. "It's an attitude adjustment," he says. "Not ever being satisfied. Things obviously have not been easy for me in my career."

What ensued over the next three seasons was arguably the greatest sustained performance by an aging athlete in the eternal history of athletes growing old -- a performance so consummate that it convinced Brady that, thanks to the TB12 Method, he wasn't really aging at all. Brady credited Guerrero for keeping his body intact, and Guerrero credited himself, but the Patriots credited adjustments Brady had made to his game. He wasn't too proud to throw the ball into the dirt at the first sign of danger, and he wasn't getting hit as much. And when the team saw how fresh his arm was at the end of a 2016 season that began with his serving a four-game suspension, talk among the coaches turned to the question that will follow Brady as long as he plays: Can he do 16 games again?

Belichick is seeking to secure an immortality of his own. No one knows how much longer he'll coach, but his friends give him two or three more years, enough to ensure that his two sons, Stephen and Brian, both Patriots assistants, are secure, and possibly long enough to establish a truly dynastic succession. He'd told friends for the past year that he wanted to coach Garoppolo as a starter and that he was confident he could win a Super Bowl with him. That, of course, would have required him to decouple himself from the player who has changed his life and his legacy, and so the question always was: Would he do it? Would he actually move on from TB12?

On the night of Oct. 30, that question was answered -- for now, at least -- when he traded Garoppolo to the San Francisco 49ers for a second-round pick. The trade came out of nowhere, surprising people close to Belichick, Brady and Garoppolo. But while it's easy to see the move as a demonstration that Brady is and always will be the one exception to the Belichick Method, it instead serves as confirmation that the Method will always win. Did Belichick trade his backup out of loyalty to a 40-year-old quarterback, or because cutting bait at exactly the right time is what he always does and always will do?

For the short term, Brady will find himself in the position of being the future of the Patriots -- with no end in sight. The Garoppolo trade can be seen as an expression of faith not only in Brady, but also in the TB12 Method. The apparent vote of confidence comes even as Brady has found himself in the middle of a conflict between the Patriots and Guerrero, with Guerrero blaming the team's trainers for injuries some of his clients have suffered and with Belichick making it resoundingly clear that Guerrero has no actual role on his staff. "There's a collision coming," a friend of Belichick's says, and even without Garoppolo itching to supplant him, Brady is aware of the competing legacies at the heart of the Patriots' historic success. He says now that he "hopes" he doesn't play for anyone else, but "I'm also not naive to think I can't."

And Brady is not the only one to have written a book. At the end of his 2005 collaboration with David Halberstam, The Education of a Coach, Belichick makes a case for luck as a prerequisite for greatness and uses Brady as the prime example. When Brady was suspended at the beginning of 2016, Garoppolo took his place, in an echo of the start of Brady's career. But there is only one Brady. Garoppolo played well, but for either a want of luck or willpower he lasted only five and a half quarters before being knocked out with a shoulder injury and eventually giving way to Tom Brady and the Method.

One day last year, the two scientists whose company created the software product Brain HQ were surprised by a phone call that came to their office in San Francisco. It was Alex Guerrero, telling them Tom Brady was using the brain exercises they'd been developing, and they were surprised for a couple of reasons. First, Brady wanted to meet them. And second, he was not using the exercises in ways for which they were intended. "We improve people who need improvement," says Henry Mahncke, CEO of Posit Science. "Old people, people who've suffered cognitive damage, but not a guy at the top of his game using our exercises to get better."

So Mahncke and Posit Science founder Michael Merzernich flew to Boston and visited Brady and Guerrero at the TB12 training center. "The first thing that was pretty wild was that they had a personal team of neuroscientists," Mahncke says. "And we're like, 'This is the kind of thing you can do when you're the greatest quarterback of all time.' But what he told us was pretty striking. He said, 'I'm at the point where I want to be the best in every possible way. I came across the exercises in Popular Science, and I can already see the difference in my brain function. This kind of brain training is like physical conditioning. It can help anyone.'

"That's just not how we thought of brain training before," Mahncke says. "If you have bad cognitive function, we can help you. But Tom was using the same exercises that people in much worse condition use. We didn't have to change the science at all. He was just using them at a totally different level."

Did Brady decide to engage in brain training because he felt himself on the verge of rising to a new level or because he felt himself falling behind as a consequence of trauma already suffered? Mahncke didn't know; he had never asked. But he wanted to make one thing clear: "I talk to Tom a bunch, and this might surprise you, but he never talks about concussions, at all."

But the question holds, because either Tom Brady is a football player who, like other football players, has suffered multiple concussions, or he is a football player who, unlike most other football players, has found a way to rise above the game's inherent assault on body and brain. It is not only his wife who says he is the former; many Broncos believe they noticed him in an all-too-recognizable daze during the 2015 AFC championship game. Yet he not only speaks in his book of his determination to stay ahead of brain injuries; he speaks unsparingly of those who let injuries get ahead of them. Famous for being unforgiving of himself when he makes mistakes, he turns out to be unforgiving of players who make the mistake of getting injured. "If our bodies can handle the force, it doesn't matter what sport we play or how old we are. That's why age isn't my problem!"

He has little sympathy for anyone whose experience might contradict the overarching TB12 narrative. "Players say the biggest reason [for early retirement] is their fear of the long-term effects of playing while injured. I don't have that fear. They have no idea they can have a body or a career free of the pain that athletes of the past have endured."

By the end of The TB12 Method, he is not even talking about injuries, trauma or even sport. He is professing his faith that "we can decelerate the aging process as most people experience it today." As an athlete, he is already an immortal, but he begins to emerge as an Immortalist too, someone convinced that the answer to the question he poses near the close of the book -- "What does it mean to naturally age?" -- is that aging is unnatural and not to be accepted without a fight. It sounds grandiose. But after the Falcons rematch, he puts the fight in a humble context:

"The reality for me is not how long I want to live but the quality of life. I love playing football, I love everything about it, I want to do it for a long time. And at the end of that, I still want to do all the things I love to do. And that's what it's about for me. It's about doing what I love to do for as long as I'm here. You can't take any of these days for granted. But I also want to do what I have to do to prevent long-term damage to my body playing sports. Afterward, I still want to be able to ski, to surf, and do the things I love to do. I still want to be able to throw the ball around with my kids and play soccer in the backyard and have fun in life."

It's not that Brady wants what no one else has. He wants what everyone else has, or thinks they have. He toys with the notion of immortality because, as a human being who has played nearly 300 games in the NFL, his mortality is demonstrably accelerated and actuarially advanced. To do a job for as long as he loves and to stay whole, it doesn't seem like much to ask. But then again it is asking for the world.

Of course, Belichick and the Patriots are also asking the world of Brady. They are not only committing to a 40-year-old quarterback; they, with the Garoppolo trade, have blocked Brady's simplest means of a graceful exit. He has decided not to stop. Now he also can't fail.

What would count as a failure for Tom Brady? Playing until he's 41 instead of playing until he's 45? Never winning another Super Bowl? Getting released at age 43 from the Patriots and spending the last days of his career hobbling around for the Browns, still angry that they took Spergon Wynn in the sixth round of the 2000 draft instead of him? Or getting all he wants -- playing until he's 45 and winning two more Super Bowls -- only to discover 15 years later that he has recurring headaches and his memory is hazy and he can't follow the route to the nearest TB12 training center?

None of these scenarios is far-fetched and none of these scenarios is inevitable, and the scenario that probably scares him the most -- the one in which, for all his investment in brain training and bioceramic sleepwear, he ends up just another athlete staying on a little too long and getting out a little too late -- is the most likely. He is so accustomed to thinking in terms of the impossible that he often forgets to think in terms of the probable, and he's so intent on thinking in terms of willpower that he misses the simple power inherent in accepting one's fate. People do run out of luck, especially on the football field. And with the Method, he defines unavoidable occurrences in his sport as failures and risks making failures of his teammates and his friends.

So let's go back to Tom Brady throwing a pass to Julian Edelman. This time they're not playing for high stakes in the Super Bowl; this time they're playing for no stakes at all, in a preseason game against Detroit. Edelman lines up in his familiar place in the slot; he dances upfield, then catches a ball Brady throws over the middle. It's an ageless play run by two men who have made ageless plays their business. Then three Lions close in. Edelman tries to do the impossible -- he tries to evade them all -- and when he pivots left, his right knee gives out, extending so unnaturally that it snaps him into the air with the force of a slingshot. He falls to the ground and rolls over clutching his knee, in an agony of ruin, knowing his season is over.

By Brady's logic, the injury could not have been a matter of luck -- there is no luck. It could not have been the game -- don't blame the game. It has to be a failure of pliability. "What will happen when an athlete with tight, dense, stiff muscles ... runs and makes a sharp cut?" he writes. "If these functions overload a muscle, bone, tendon or ligament, he will get injured." But here's the problem: Edelman practices pliability. He "certainly gets some deep-force muscle work," Brady says. How then can Edelman have failed?

But then something else happens. Over the course of the season, even as Brady maintains an MVP-level form, others go down -- all members of the pliability circle. Hightower with a knee issue and a pectoral tear. Amendola with a concussion. Gronk with a groin problem. Brady himself has an aching shoulder. But he not only keeps showing up, he keeps prevailing, left alone with his Method, his singular talent and his unflagging determination. The game might never beat TB12. But it will do its best to make him the last man standing.

And the Falcons became Super Bowl LI Champions of the First Half

Brady can still throw it and, although they pretend to try, QBs don't tackle those that pick them off. George Blanda was around 46 before he retired, although admittedly he mostly kicked, he did play some at QB when the need arose.

Brady might be the greatest QB of modern times, but he cannot run out the clock on this game......................

Tom Brady rarely gets hit or sacked, he rarely scrambles, and the Pats never give him plays where he runs the ball.

The brutal, knee-smashnig, concussion-causing game of football is an entirely different game for him.

His value is in his judgement and ever-increasing experience in the game, not his athletic ability.

He made his debut in the National Hockey League in 1990, and he just started his 27th season of professional hockey at the age of 45. I'd suggest hockey is a much more difficult game for anyone to play, and to do it at that age is beyond outlandish.

P.S. -- He has worn #68 for his entire career, in honor of his grandfather who died in a Czechoslovakian prison during the Prague Spring uprising of 1968.

If a QB falls in the forest with no one around, does he make a sound?

This article really tested me. The first half reads like it was written by a pair of homos. But the last quarter or so gives Brady his due.

It is a bit long and somewhat repetitive

Long articles are difficult for me b/c I tend to

Long long read. Why couldn’t you have just excerpted it?

Well the Patriots just traded their promising, and proven, backup QB, Garapollo, away a couple of days ago, so Bellichick may not share that opinion.

BUT, when a guy gets "old" it sometimes happens all at once, and I can attest to the fact that you don't heal or bounce back as fast.

It's From ESPN, they probably are................

He’ll be the healthiest guy wandering around his own neighborhood trying to remember which house is his.

Brady will play until he can play no more. Then he will sign with the Cardinals.

Is it shorter on another site?

Is that an accurate portrait of Brady or have they taken liscence for effect? I’d be shocked if he really looked that bad. He’s only 40.

Brady may not be the most athletic QB, but the guy is amazing when he moves around in the pocket. There are times I swear the dude has eyes in the back of his head. I’m not a Patriots fan, but it will be sad to see Tom Freakin Brady go.

Didn’t want to give ESPN the clicks?

Jagr is phenomenal. But Brady plays every snap (when he’s not hurt) while Jagr’s playing time isn’t what it used to be, and Brady gets pummeled by huge linemen (nobody really checks Jagr anymore). What Brady is doing is unprecedented, but will happen more as time goes by and more athletes copy his methods.

Note the date on the mag.................2022...............

Jagr was averaging 17 minutes of time on ice per game as recently as last season. He's down to 11:00+ this season, but the Flames kept his playing time down early on because he was a late signing and wasn't in training camp.

Disclaimer: Opinions posted on Free Republic are those of the individual posters and do not necessarily represent the opinion of Free Republic or its management. All materials posted herein are protected by copyright law and the exemption for fair use of copyrighted works.