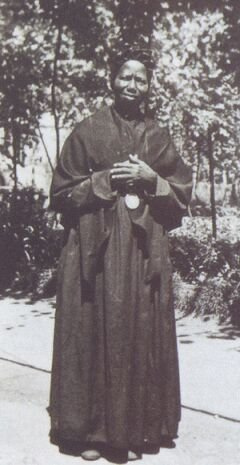

Saint Josephine Bakhita

Giuseppina Margherita Fortunata

Josephine was a twin, child of an African family of property. When she was kidnapped into slavery, Sudan wasn't yet a country. She saw one of her group of fellow slaves severely beaten and abandoned to die. She suffered great cruelty from Turkish owners and was viciously, ritually scarred all over her back. She became the nanny of the daughter of Italian owners. While her mistress returned to Africa, she was left with the baby girl at a convent in Italy where she became Catholic. When her mistress returned to take her and the child, Josephine resisted leaving because her religious education wasn't finished and she wasn't ready to be baptized. Her mistress tried to force her to go back to slavery in Africa, but the Archbishop Patriarch of Venice defended her, since slavery was illegal in Italy. She became a Canossian Sister. She cared for invalid soldiers in World War I. She became famous because of a book written about her by an Italian journalist in 1930. She was sent on a public speaking tour but had stage fright. She remarked about her enslavers: "If I were to meet those who kidnapped me, or even those who tortured me, I would kneel down and kiss their hands. Because, if those things had not happened, I would not have become a Christian and would not be a Sister today."

“The law of the Lord is perfect, it gives wisdom to the simple.” (Ps 19: 8)

“These words from today's Responsorial Psalm resound powerfully in the life of Sr Josephine Bakhita. Abducted and sold into slavery at the tender age of seven, she suffered much at the hands of cruel masters. But she came to understand the profound truth that God, and not man, is the true Master of every human being, of every human life. This experience became a source of great wisdom for this humble daughter of Africa.” (Extract from the Homily of Pope John Paul II at the Canonization of St Josephine Bakhita)

Children arriving for the first time at the Canossian Convent in Schio - to be enrolled in the day school or nursery, or the boarding unit, or just to take part in a sewing class or a youth club - were usually startled to find that one of the nuns was black. This was in the 1920s and 1930s and hardly anyone in this quiet little north Italian town had ever seen a black person before. Very small children had been known to run away screaming in terror. But the kindly African Sister never seemed embarrassed, and soon put them at their ease. All of them quickly grew to love her, and whenever she appeared they flocked to her side. It was customary to address the nuns as “Mother”, and properly-speaking she should have been Mother Josephine. But everyone called her “Black Mother”.

Every Sunday the children besieged her, clinging to her long skirts and clamoring for a story. Black Mother's stories left behind the same deep-down, satisfying feel as a good fairy tale. The fact that they didn't have any fairies in, and had happened “for real”, was completely beside the point. Fairy tales come in all shapes and sizes, but essentially they offer assurances about life. A typical scenario has a young person leaving home, sometimes very abruptly, to go out into the big wide world, and there face a series of apparently insuperable obstacles. But the obstacles can be overcome, and overcoming them wins the reward of a kingdom and an ideal marriage and being “happy ever after”. The underlying message is: “Don't be afraid, because a kind providence is watching over you, and - you'll see - everything will work out in the end.”

|

|

Beginnings

“My family lived in the middle of Africa ...”

Black Mother knew precisely where she was born: a village called Al-Qoz in Darfur. Its name meant “Sandy Hill”, and it stood at the southern edge of the Sahara Desert in an area of rolling countryside known as Daju, almost exactly halfway between the continent's eastern coastline on the Red Sea and its western coastline on the Atlantic. She couldn't give the date of her birth, but it was guessed to be 1869. Her father was a landowner with a large staff of field labourers and herdsmen, and the village head man was her uncle. Clearly her family was economically well-off, but more importantly it was close and loving: “It was made up of father, mother, three brothers and three sisters, plus four others whom I never knew because they died before I was born. I had a twin sister; I've no idea what became of her, or of any of them, after I was stolen. I was as happy as could be, and didn't know the meaning of sorrow.”

Today Darfur is part of Sudan, the largest country in Africa, covering 967,500 sq miles, but before the nineteenth century this vast territory, populated in the north by arabised Muslim tribes, and in the south by a great many different cultural and language groups which kept to traditional animist religions, had never been a cultural or political unit. Even in 1869 Darfur was still a small, independent sultanate, dominated by a tribe called the Fur from their strongholds in the high mountains of Jabal Marra to the north. The Fur had long been Muslim, but their subject peoples did not necessarily share their religious allegiance: the inhabitants of Al-Qoz, at that date, were not Muslims. In her reminiscences, Black Mother said nothing of structured religious observances. She did speak very vividly, however, of her own awakening spiritual awareness in response to the world around her:

“Seeing the sun, the moon and the stars, the beauties of nature, I asked myself, ‘Who is the owner of all these beautiful things?' and I felt a great desire to see him, to know him and to pay him homage.”

The little girl had no idea of the political developments, far to the north, which were about to impact on Darfur. Guglielmo Godio, an Italian explorer who visited the Sudan during the second half of the 19th Century, spoke cordially of the Sudanese people, whom he found "naturally good, hospitable, and loyal." Godio described the Sudan as a mysterious country, where men carried long arrows, huge swords, and heavy shields made of buffalo, hippopotamus and elephant skin. Their bodies were lithe, their bearing proud, and their hair thick, rough and curly. To a stranger encountering them, they might look frightening, but they were basically kind and reliable. The women were reserved and possessed a dignity of their own - on them fell the heavy duty of drawing water from wells, which were often remote from the villages. They carried the water in goatskins, which were known locally as "ghirbe." Hunting with javelins and arrows was popular with the villagers, though their main occupation was breeding cattle and sheep.

In medieval times, the country was known as Bilad-as-Sudan, which means "country of Blacks." People living in the south are very dark; in the north, because of the interactions with neighboring Egypt, the people's appearance is more Arabic. In fact, the Sudan's history is closely related to that of Egypt. Since 288 B.C., echoes of the pharaonic glories had reached the Sudanese people through the tortuous but convenient Nile waterway. Ancient monuments discovered in Bakhita's country bear unmistakable witness to Egyptian influence on its history.

After conquering Egypt, the Romans attempted to penetrate into the Sudan. In 66 A.D., the Emperor Nero dispatched two centurions to explore the land for possible conquest. The explorers, however, reported that the country was too poor, and not worth invading. Apparently, these couriers never went beyond the Nubian Desert, so their report may have been somewhat inaccurate. Other powers thought differently. In the 7th Century, after conquering Egypt, the Arabs pushed further south into Nubia and established a regular slave trade, which was to last for centuries.

In 1805 Islam was forced upon on the conquered people. Turkey conquered the Sudan, and Mohammed Ali, a soldier in the Ottoman army, seized power in Egypt and forced the Sultan of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) to recognise him as governor. Mohammed Ali was installed as Khedive. Neither he, nor any of the administrative and military leaders who rose to power with him, were Egyptian: they had all come from other parts of the Ottoman Empire to make their fortunes. Because the language they spoke among themselves was not Arabic but Turkish, they were generally referred to as “Turks”, though often they were European Muslims: Muhammad Ali himself hailed from Macedonia. Once his position in Egypt was secure, he tried to expand into the Middle East, but was warned off by the European powers. So he turned his attention southwards up the Nile where, from 1820, he began carving out for himself a huge central African colony: Sudan.

In Sudan the Turks behaved like robber barons, unashamedly out to plunder the country for all it was worth, for the personal enrichment of themselves and Muhammad Ali. They had hoped to find gold, but there wasn't much there: the main form of wealth was slaves.

Muslim Sudanese could not legitimately be enslaved themselves, but were quickly forced to hand over a large proportion of the slaves who constituted their household retinues and labour force. The only way to reimburse themselves, and continue to meet the Turks' insatiable demands, was to seize increasing numbers of fresh slaves from among the “unbelievers” further south.

Muhammad Ali's successors, who ruled as hereditary governors of Egypt enjoying the title “khedive”, were eager to adopt new technological and educational ideas from Europe and, together with the rest of the ruling class, became increasingly westernised in their outlook. Meanwhile the subjugation of Sudan continued but, as the western nations successively repudiated slavery, its continued prevalence in their dominions became an acute embarrassment to the khedives. Measures were launched to develop the Sudan economically, partly in the hope that the growth of “legitimate” trade would squeeze out slaving, and also to make it into a steady source of wealth to pay for Egypt's modernisation programme. Better agricultural techniques and new crops were introduced, and traders ventured up the Nile in search of ivory. Another eagerly sought-after product was gum-arabic, an exudate of the acacia senegal tree, used since ancient times as a food additive and in pharmaceuticals. Nevertheless, alongside all this “legitimate” economic activity, the slave trade continued to flourish.

African slavery took many forms, some of them relatively benign. Slaves in traditional societies were not necessarily ill-treated, and might live as subordinate members of extended households in conditions which compared very favorably with those of factory workers in nineteenth century Britain. But whenever slaving was driven by strong outside forces it necessarily entailed tremendous suffering, due to the violent measures used to obtain captives, and the brutality with which they were conveyed over long distances to the place of sale. Under pressure from international public opinion, the khedives began introducing anti-slavery measures, but these proved ineffectual. Because the Sudan was so vast, raiders and traders could usually evade police patrols.

Khedive Ismail, who succeeded in 1863, was determined to confer on his dominions the full benefits of western civilization and, having come to the conclusion that his fellow-Turks were too inefficient and corrupt to accomplish the task, resolved to employ as his agents European Christians. During the ceremonies for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which were graced by the presence of a glittering line-up of eminent Europeans, he successfully recruited the British explorer Sir Samuel Baker. Baker's mandate was to consolidate Egyptian rule over the whole of the Nile basin, and suppress the slave trade. He and his successor, fellow-Briton Charles George Gordon, greatly expanded Ismail's Sudanese empire, but completely failed to eradicate slaving. They merely rearranged it, driving the slavers away from the Nile to the overland routes through western Sudan.

In 1874, shortly after Gordon's arrival, Sultan Ibrahim Muhammad of Darfur was defeated and killed in battle by the notorious slave trader Zubayr. Darfur was absorbed as a Sudanese province, and from then on slavers from other parts of Sudan were free to raid into it.

It was at this time and in this place that the history of Catholic missions in Africa meets Bakhita's personal history. Her forced march began at Olgossa, a village close to Agilere Hill, facing Mount Marra. Through various stages, filled with suffering and agony, her journey was to reach Kordofan, where Comboni's followers worked. Of course, Bakhita was never aware of their presence. As a slave, she would never be allowed to leave the duties imposed on her and step out of the house; even if she had been next door to a Catholic Church, she would have had no chance to see it. She could truthfully state that she "had no idea of God," and that her family "did not worship idols."

From it all, we can deduce that her people professed animism, a religion common to African tribes even today. Animism boasts of no founder, no prophet; its tradition is based on experience accumulated through centuries. The cult is for ancestors within the family, the village, the tribe. Its manifestations change from place to place, to the extent that the variety of its expressions is almost unlimited. Animism attributes a soul not only to men, but also to animals, plants, and inorganic matter. As far as man is concerned, animism teaches the survival of the soul in an ultra-terrestrial life. The soul is conceived in the function of the respiratory process; once this ceases, life ceases also. From the elusive lightness and volatility of breath springs the idea of an immaterial soul, alive and vigorous in all the manifestations of natural life. Such a conception obviously leads to the cult for the spirits of the dead, and to a deep respect for those who are closer to them - unborn babies and the aged. Hence, great honor is paid to motherhood, and to all the manifestations of nature.

This was the socio-religious structure of the tribe from which Bakhita arose. Thus, she was right when she stated that she had never worshipped idols. On the other hand, she often expressed her deep regret at having known no faith in moments of her life when she needed it most. She once said,

"Had I known that there was a God during my long years in slavery, my suffering would have been lessened."

The Daju Hills would have been arid and bare but for the many streams flowing down from Jabal Marra. Fertile patches spread out on either side of the streams, and so Al-Qoz was surrounded by beautiful greenery. In Black Mother's story, the occasion on which she first learned the meaning of sorrow began with a happy outing in this lush countryside.

“One day my mother decided to go out into the country where we had many fields full of crops, and herds of cattle, to see if all the workmen were attending to their tasks. She wanted all us children to go with her. But the eldest girl, who wasn't feeling well, asked if she could stay at home with our little sister, and Mummy agreed. While we were out in the fields we heard a great commotion: lots of shouting, and people running to and fro. Everyone immediately guessed what it must be - slavers raiding the village.”

Rushing back home, they found the little sister - Black Mother's twin - shaking all over with terror. She'd managed to hide behind a broken-down wall, so the raiders hadn't found her, but the older girl had been taken.

“I still remember how Mummy cried, and how we all cried. That evening, my father came home from work and heard what had happened. He flew into a rage, and immediately set out with his men to search all around, but in vain: we never heard anything of our poor sister ever again. That was my first sorrow and oh, how many, many more lay in store for me after that. One morning when I was about nine years old I set off after breakfast with one of my friends, who was twelve or thirteen, for a walk in our fields a little way away from home. After playing for a while we broke off, and became absorbed in gathering herbs. All of a sudden two ugly armed strangers emerged from a hedge. Coming up to us, one of them said to my friend: ‘Let this little girl go over there to that wood to fetch a package for me. She'll come back straightaway. Carry on walking and she'll rejoin you in a minute.' Their plan was to get my friend out of the way, because if she'd been there when I was captured she'd have given the alarm.”

Although when telling the story years later, Black Mother thought she had been nine at the time, it is more likely that she was only seven.

“I didn't suspect a thing. I went to do as I was told, just as I did for my Mummy. Hardly had I gone into the wood to look for the package, which I couldn't find, than I saw those two coming up behind me. One of them grabbed me roughly with one hand; with the other he drew a big knife out from his belt, pointed it at my side, and snapped: ‘If you shout, you're dead! Move! Come with us.' The other man pushed me forward, digging the barrel of a gun into my back. I was petrified with fear, my eyes staring, trembling from head to foot. I tried to scream, but there was a lump in my throat: I couldn't speak or cry out. Brutally driven into the thick of the wood, by hidden paths, across fields, they kept me going at a forced pace till evening. I was tired to death. My feet and legs were bleeding, because of the sharp stones and the prickles of the thorn bushes. I was sobbing my heart out, but their hard hearts felt no pity.”

A new name

Dusk was falling as the three emerged from the far side of the forest. Still they didn't stop, but the man holding the child suddenly paused and asked her what was her name. She tried to answer but her voice wouldn't come out properly. The other man snapped, “Call her Bakhita and don't waste any more time on that snotty kid.” He shook his whip in her face: “Understand? From now on your name is Bakhita. Don't forget it!”

It meant “Lucky”, and as such it was a very common name for slaves, because owners liked their slaves to bear auspicious names. Similarly, in the time of the Roman Empire, slaves were given names like Felix and Felicity. One of the most revered early Christian martyr-saints was Felicity, a slavewoman of Carthage in Africa.

“At last we took a break to get our breath back, in one of the fields full of watermelons which grew in great abundance in the countryside through which we were passing, The men picked some fruit and gave me a piece to eat. But I could hardly swallow it, even though I'd had nothing to eat since morning. I couldn't do anything expect think about my family. Heartbroken beyond all words, I kept calling out for my Mummy and Daddy, but they couldn't hear me. In any case the men made terrible threats to shut me up and, tired and hungry as I was, forced me to my feet again. The journey went on all night. At first light we entered their village. I couldn't possibly have gone any further. One of them grabbed me by the hand, dragged me into his house and thrust me into a poky storeroom, full of tools and broken bits and pieces. There weren't even any sacks to lie on, or anything I could use as a bed: nothing but the bare ground. He gave me a piece of black bread and said, ‘Stay here'. Going out, he locked the door with a key. I was there for over a month. A small opening high up above was my window. The door was opened briefly from time to time to give me scraps of food. How I suffered in that place I can't put into words. I still remember all those terrible hours during which I exhausted myself with crying, eventually collapsing on the ground in a light swoon. Then my imagination took me among my own dear ones far, far away: I saw my beloved parents, brothers and sisters, and embraced them all with joy and tenderness, telling them how I'd been kidnapped and how much I'd suffered. At other times I imagined myself playing with my friends in our fields and felt happy. But woe is me, whenever I came back to the harsh reality of that horrid loneliness, a sense of despair came over me which seemed as if it would break my heart.

“One morning the door was opened earlier than usual. The master presented me to a slave merchant, who bought me and put me together with some other slaves of his. There were three men and three women, and a girl not much older than me. At once we set off. Seeing the countryside, the sky, water, being able to breathe free air gave me back a bit of life, even though I didn't know where we were going to end up. The journey lasted eight days non-stop. Always on foot through woods, over hills, through valleys and desert places. I'll describe how the caravan was organized. The men went in front and after them the women, linked together by great chains padlocked round their necks, either into pairs or into groups of three. If anyone turned or stopped, heaven help his poor neck and that of his companion! You could see round each person's neck big, deep sores that made you feel so sorry for them. As we went through village after village the caravan kept getting bigger. The stronger men were made to carry great loads on their shoulders for mile after mile, poor things, as if they were pack animals. We children weren't chained; we walked near the back, in the midst of the masters. The caravan only stopped a few hours to rest and eat, and at those times the chains were taken off the slaves' necks and put round their feet, a pace apart from each other, to prevent escape. They did that with us children too, but only at night.

“At last we stopped at the slave market. We were all put into a large room to await our turn for sale. The first to be sold were the most weak and sickly, for fear they would get worse and nothing could be had for them at all - poor victims! We two children - the girl who was about my own age, and me - found ourselves always together, because our feet were fastened together by the same chain. Whenever nobody was listening, we used to talk to each other about how we were stolen. We spoke of our dear ones, and the longing kept welling up inside us to return to our families. We wept over our unhappy fate - but at the same time, we were putting together a plan for flight. The good God, who watched over us without us even knowing it, gave us the chance: this is how it happened.”

Escape

“The master had put us in a separate room and always shut us in, especially when he had to leave the house. It was nearly suppertime when he came back from the market leading a mule laden with maize. He took our chain off, ordered us to husk the corn-cobs and feed some of them to the mule, and absentmindedly went away without closing the door. We were alone without the chain. In the providence of God, this was our moment!

“We looked at each other, linked hands, looked around and saw nobody, then were off into the open countryside, with no idea where we were going but with all the speed our poor little legs could give us. All night long we ran and ran, driven on by terror, in and out of the woods and through the desert places. Gasping for breath, we could hear in the darkness the roaring of wild beasts. Whenever they came close we climbed up into the trees for safety. One time we had just got down from our refuge, and carried on running, when we heard the typical hum of an approaching caravan. We hid behind some bushes bristling with thorns. For a good two hours one group after another passed just in front of us, but nobody saw us. It was the good God who protected us, nobody else.”

Lost in the pitch dark forest, surrounded by perils worse even than brutal and greedy human beings, Bakhita suddenly saw a beautiful form appear in the night sky above, bathed in light and smiling down at her, pointing which way they should go. Without any explanation to her companion, who obviously saw nothing, she led them both in the direction indicated until, as dawn approached, the apparition vanished. This experience touched Bakhita very deeply, so much so that she could almost never bring herself to speak of it. Years later, however simply and openly she told her story to those who asked, whenever she got to this point she automatically left out the shining figure: she only ever mentioned it very privately, to a few people. At the time she'd been unable to make any sense of the experience, but now she knew it had been a vision of her guardian angel. The angel had guided her out of the forest and towards the right path: the path chosen lovingly by God for her to walk along - though, as she was to discover, it did not lead back to the home she had left.

“I made myself believe that once I'd got through the dangers I would quickly find my dear ones. This hope made me willing to suffer everything, and kept up my spirits. Alas, far from drawing nearer to them I was running I don't know how much further away … Towards dawn we stopped and took breath. How tired we were! Our hearts were hammering inside our chests, great drops of sweat trickled from every pore, a ravening hunger tore at our stomachs: we had nothing to eat. The longing to see our families again, and the fear of being caught, gave us strength to continue running, though not like before. But where would we end up?

“Towards sunset we saw a cabin. Our hearts leaped and we strained our eyes to see if it was our house. It wasn't - imagine our bitter disappointment! As we stood there thinking what to do next, a man appeared in front of us. Frightened, we made to run, but blocking the path he asked us, in a nice sort of way, ‘Where are you going?' We remained silent. ‘Come on,' he said, ‘where are you going?'

“‘To our parents.' ‘And where are your parents?' ‘There.' we replied, pointing confusedly without knowing where. Then he realized we were fugitives. ‘OK', he said. ‘Come and rest a bit. Then I'll take you to your parents.'

“Believing what he said, we followed him into the cabin. As soon as we entered we collapsed on the ground, completely done in. He gave us some water to drink, but we were so far gone we could hardly swallow. Then he left us alone and in peace, and we slept for about an hour before he woke us up, took us to his house, gave us food and water, and then put us into a big sheepfold full of sheep and goats. He made space to put down an angareb (string bed) and then, fastening us together by the feet with a heavy chain, told us to stay there in the sheepfold until further notice.”

Slaves again

“That was that - we were slaves again. So much for taking us to our parents. We cried and cried. He left us there among the sheep and lambs for several days until a slave merchant passed, then took us out of the sheepfold and sold us to him. We had to walk a long way before rejoining the caravan. Imagine our surprise when we saw, among the slaves, some who had belonged to the master we'd escaped from. They told us how furious he'd been, and what a hue and cry there was when we weren't found. He was blaming and hitting out at everyone he met, and threatening to cut us into pieces if he found us. Now I understand more and more the goodness of the Lord who saved me then so miraculously.”

The rage of their previous owner isn't surprising, since Bakhita and her friend were the pick of his stock. Children between the ages of about ten and fifteen fetched the highest prices: he'd been hoping for far better profits on them than on the adult captives. Girls were at least as valuable as boys in Sudanese slave markets, and in Egypt and Arabia were usually more in demand.

“We marched on for two and a half weeks, always with the same order as described before. During that journey I was touched to see one poor slave who was in so much pain he could no longer stand. He begged to be allowed to sit and rest for a while, but the master refused to believe him, and hit him as if he was an animal. I saw him fall to the ground wailing, ‘I can feel myself dying, I can't go on.' But that monster only beat him all the more, to make him get up. However, seeing that he really couldn't move, he had no choice but to take off the chain that linked him to his companion. The poor man moaned and pleaded for mercy but the master, filled with rage, ordered us to keep going while he stayed with that wretched slave. What did he do to him? Nobody ever saw him again. Arriving at last in the city, we were taken to the house of the Arab chief.”

Since she was kidnapped Bakhita had been forced to cover on foot almost 600 miles - not counting the escape attempt. The city was El Obeid, provincial capital of Kordofan. Kordofan was - and still is - the world's biggest producer of gum-arabic, and El Obeid its principal market. At that time it was the wealthiest town in Sudan, with a higher population than any other settlement: over 100,000 people.

In the household of the Arab chief Bakhita was initiated into her new existence, quickly becoming fluent in Arabic and forgetting her original language.

“He was a very rich man who owned a large number of slaves, all in the flower of youth. My companion and I were assigned, for the time being, as handmaids to the ladies and his daughters, who took a liking to us. It was the master's intention to make a present of us to his son on the occasion of his marriage. In that house we were treated well, and lacked for nothing. Only, one day I committed some fault in the eyes of the master's son. He immediately seized a whip to flog me. I fled into the other room to hide behind his sisters. I should never have done that! He flew into a rage, dragged me out of there, flung me on the ground and with the whip and with his foot gave me so, so many blows. Finally, a kick to my left side made me lose consciousness. The slaves had to carry me to my sleeping-mat, where I lay for over a month.”

We have already said that Bakhita was very common as a slave-name. At this point in the story, let's take a look at another Bakhita who was living in El Obeid at this time. She had been born in Tongojo in the Nuba Mountains, kidnapped from there in 1854 when she was around twelve, and eventually sold in Egypt, but very soon after the original sale she was repurchased by a Catholic priest named Nicolò Olivieri. Her original name before she was captured by the slavers was Kwashe.

Fr Olivieri, then already in his sixties, had dedicated his life to ransoming slave children, and for that purpose set up extensive fund-raising and support networks in Italy and Germany. After his death his work would be carried on by another Italian priest named Biagio Verri, and between them they must have rescued about 1,200 youngsters, arranging for them to be brought up and educated in Catholic orphanages and boarding schools in Europe.

Mostly they ransomed girls, even though girl slaves cost more, because they were easier to place. Olivieri's work was praised by a number of influential Catholic leaders, including Don Bosco, but it also attracted sharp criticism. A very high proportion of the rescued children could not cope with the European climate, fell ill and died. The survivors, having completely lost touch with their roots, couldn't re-settle in Africa - but their institutional upbringing had isolated them from normal life in Europe too, so that they didn't seem to belong anywhere. A significant number resolved their dilemma by entering the religious congregations which had brought them up. Others fell in with plans laid for them by their educators that they should return to Africa as lay missionaries. These developments gave rise to further criticism, since their options appeared too limited for them to have made a truly free choice. Nevertheless, there were a few undoubted success stories - and Bakhita Kwashe was one of them.

Maddalena di Canossa

Verona was a vibrantly Catholic city which had produced an impressive number of new initiatives to address the changing needs of the Church and the world. One was the Daughters of Charity, commonly known as Canossian Sisters after their foundress Maddalena di Canossa.

Another was the Mazza Institute, which offered an excellent boarding school education, completely free of charge, to both boys and girls, and fostered a great many vocations to the priesthood and religious life. Its founder and director, Fr Nicola Mazza, agreed to give about fifty places to African girls - his intention being to groom them as auxiliary missionaries, to assist some of his students who were planning to go out as priests to Sudan. Bakhita Kwashe was among the first batch.

Vinco and Knoblecher

At a time when most parts of the African interior were so completely unknown, it had seemed a very good idea for a pioneer missionary expedition to aim for Sudan, ruled as it was by a government which enjoyed diplomatic relations with Europe. This expedition, which set out in 1847, was made up of volunteers from several different countries under the leadership of Maximillian Ryllo, a Polish Jesuit with long experience in the Middle East. It succeeded in reaching Khartoum, the administrative capital of Sudan situated at the confluence of the White and Blue Niles.

So far Khartoum was little more than a shanty town, and they set up their base in tents by the river bank. However the principle obstacle to European penetration into the heart of the continent remained the lack of immunity to its endemic diseases - particularly malaria. Very quickly Ryllo fell sick and died. Fr Angelo Vinco, an ex-student of the Mazza Institute, was ordered to return to Europe accompanying another sick missionary, leaving a Slovenian priest named Ignaz Knoblecher in charge.

Despite the unpromising start, Vinco had fallen in love with Sudan. Suddenly reappearing at his old school, he inspired the director and many of the current students with his own enthusiasm. So it was that in January 1849 a 17- year-old philosophy student named Daniele Comboni knelt down before Fr Mazza, and vowed to devote his life to bringing the Gospel to central Africa.

Vinco meanwhile had made his way back to Sudan. He and Knoblecher then embarked on an historic journey up the White Nile to Gondokoro, where the Bari people lived. Before then, no white man had ever penetrated so far south. Vinco later journeyed south again, alone, and spent two years at Gondokoro, learning the Bari language and trying to present the Christian message to them in terms they could understand, until in January 1853 he fell ill and died. He was 33.

After his ordination to the priesthood in 1854, Daniele Comboni returned to the Mazza Institute as a teacher to find Bakhita Kwashe in his class: she was probably the first African with whom he had ever come into direct contact. In 1857 he and some other ex-students set out for Sudan. On their way up the Nile they met a gaunt but venerable figure dressed in Arab robes: it was Knoblecher. He was heading north for Europe, planning to recuperate his health and regalvanise the mission's support networks, but - though not yet forty - he was in fact dying, and would never return to Africa.

The Mazza priests took charge of a mission called Holy Cross which had been established among the Dinka people, but all of them soon came down with malaria and dysentery; after less than a year they were ordered to return to Europe. The Central African mission was reassigned to the Franciscan Order, which rapidly sent in 52 missionaries. Whereas previous expeditions had travelled slowly, taking frequent rests during which they could adjust to the climate, the Franciscans raced up the Nile as fast as possible. Within a few months over half were dead. Horrified, Rome ordered the mission abandoned.

Plan for the Regeneration of Africa

St Daniele Comboni

Nevertheless Comboni refused to give up. In September 1864, while praying for Africa at the tomb of St Peter during a visit to Rome, various ideas which had been tossing around in his mind came together. He set them down on paper as a Plan for the Regeneration of Africa, and quickly obtained appointments to discuss this Plan with the cardinals responsible for overseas mission, and with the Pope personally. It sought to build on previous experience, and learn from the mistakes that had been made. Mazza's vision of forming young Africans as evangelizers to their own people was retained, but some way must be found to educate them without taking them out of Africa. As for European missionaries, they must be enabled to acclimatize gradually before going into the interior, and never spend too long there without breaks to recuperate. Comboni's answer to both needs was to set up halfway houses on the “edges” of Africa.

He set up the first one in Cairo in 1867: a large campus with a church, residential accommodation, schools and workshops. To run the girls' school he brought in some Syrian, Arabic-speaking Sisters of St Joseph of the Apparition, and fifteen Europe-educated African girls of whom Bakhita Kwashe was one. In the same year, back home in Verona, he set up an institute to train further missionaries. He himself continued to travel around Europe, and backwards and forwards to Africa, consulting all sorts of experts, picking up ideas and consolidating contacts. Some people said he was crazy, others were impressed. The Bishop of Verona, Luigi di Canossa, admired his zeal and extended the necessary authorisation for his missionary endeavours. Since Comboni was having to spend quite a lot of time in Rome anyway, Canossa tasked him with helping to push forward the canonization of his aunt Maddalena.

Missionary work required money. Comboni worked hard to reactivate Olivieri's support networks, and persuaded the Austrian Emperor, Franz-Josef, to confirm his continued patronage of those established by Knoblecher in central Europe. Imperial protection, as well as stimulating fund-raising efforts, would secure for the mission the good offices of the Austrian consuls in Cairo and Khartoum.

The Verona Missionaries

In 1870 Comboni addressed an impassioned appeal for Africa to the First Vatican Council, gaining the support of the Pope and two hundred of the Council Fathers for the reopening of the mission. Later that same year the first four missionaries trained in his institute in Verona travelled out to Cairo, and began making exploratory tours into Sudan. Meanwhile Comboni also began training Sisters. The men and women who graduated from his institutes would eventually form a religious congregation: the Verona Missionaries.

At last, after years of careful planning and preparation, in 1873 Comboni returned to Khartoum, which was now an established city with 60,000 inhabitants. He re-occupied Knoblecher's mission centre there, as a base to handle communications and logistics, but quickly moved on to El Obeid to open what was to be his main mission: besides being a much healthier place to live than Khartoum, it was strategically better placed for access to the non-Muslim population of the Nuba Mountains. He used his good political connections with the khedival government to have slave raiding and trading in and around El Obeid declared illegal; however, like other such declarations, this proved a dead letter.

Whatever starry-eyed ideas might be entertained by anti-slavery campaigners in Europe, everyone on the ground in Africa knew that freeing slaves, once they had been brought thousands of miles across the continent, was highly problematic. Even if overwhelming military force could be deployed to overcome the objections of powerful slave-masters, the captives could not be returned to their original homes. Slavery in Sudan was so closely bound up with the whole social and economic system that “freed” slaves usually had no alternative way of making a living, so that their best option might be to stay with their owners.

The Verona Missionaries recognized the impossibility of abolishing slavery overnight, but they were prepared to offer sanctuary to runaways who claimed to have been subjected to physical cruelty by their owners. The right of the missions to offer sanctuary was supposed to be upheld by the Austrian consul, but it was contrary to Egyptian law and extremely difficult to implement.

Comboni’s missions always included schools. Muslim children were not supposed to attend them, but the traders resident in Sudanese cities included Copts from Egypt, and other Christians from the Middle East and Europe: their children provided the core intake. To them were added slave children, ransomed as and when funds were available. Among the pioneers of the El Obeid mission was Bakhita Kwashe, now an experienced teacher. The mission schools flourished, and she greatly enjoyed her work. When, a few years later, the first contingent of women missionaries trained by Comboni arrived in El Obeid, she got on so well with them that she decided to join their congregation, so becoming the very first African Verona Sister.

It is no disparagement of the love and courage shown by these early missionaries to recognise that any good they could do was only the tiniest, tiniest drop in the ocean. Out of El Obeid's 100,000 inhabitants, four in every five were slaves. Whatever success the missionaries had in rescuing a handful of individuals out of this vast number, the younger Bakhita whose story we are following was not one of the handful. She was completely unaware of the existence of the Christian mission, which as far as she was concerned might as well have been on another planet.

A new master

“When I had recovered from the thrashing, I was put to other work. But my destiny was marked: I was to leave that house at the earliest opportunity. The opportunity came three months later, and I was sold to a new master, a General in the Turkish army. He had his old mother and his wife living with him. Both of them were dreadfully cruel towards the poor slaves, who were kept constantly hard at work in the kitchen, laundry and fields. I and another young girl were put at the service of the two ladies. We couldn't leave them even for a moment: what with dressing them, fanning them and perfuming them, we never got a break. And woe betide us if accidentally, perhaps because we were so short of sleep, we hurt either of them the tiniest little bit: the lashes fell on our backs without mercy. In the whole three years I was in their service, I don't recall having got through a single day without a beating: no sooner did my wounds heal than more lashes rained down on my back - without my even knowing why.

“One day I was telling my companion how I ran away from my first master. The General's daughter heard everything and, for fear I might try to escape, she made me wear a great chain on my foot. I had to drag it round for over a month. It was only taken off on the occasion of a great Muslim feast, when they were supposed to release all the slaves from their shackles. Every day the slaves had to get up at dawn. The lady, the General's wife, was so zealous that sometimes she got up before everyone else, to keep watch in case anyone was even a minute late. Then she was after him with the whip, making him leap with pain. She never cared how late into the night the poor wretch might have had to toil the previous evening. The slaves all slept in a dormitory. We got nothing to eat until midday, when each of us was given a portion of meat stew, corn meal, bread and fruit. In the evening a scanty supper, and then to rest on the bare ground. Woe betide anyone who didn't keep absolute silence. Poor victims of human tyranny! Anyone who fell ill wasn't even looked at but just left there without treatment or help. Anyone who died was thrown into the fields or onto a rubbish tip.

“How much ill-treatment and whipping we poor slaves received, without any reason! For example, one day we found ourselves present by chance when the master had a row with his wife. To work off his bad temper he ordered us two to go down into the yard, and commanded two soldiers to fling us on the ground face up to be flogged. The soldiers set about the cruel torture with all their might, leaving both of us bathed in our own blood. I can still remember how the cane, aimed again and again at my thighs, was taking out skin and flesh, and gouged out a long narrow wound which pinned me down on in my sleeping mat for months, unable to move. I had to bear everything in silence, because nobody came to dress our wounds or give us any word of comfort. Many of my companions in misfortune died under the blows they suffered.”

Most of the children had heard the story many times before, but even those hearing it for the first time weren't upset or frightened. They knew this was a good story, a story with a happy ending. Everything came right eventually.

Tattooed

Black Mother had scars and marks all over her body. They were normally hidden under her enveloping habit, but the smaller children all knew about them and often begged her for a look. Although it embarrassed her to have to unbutton her clothes even a little way, she usually gave in and let them have a quick peep. If anyone asked about it, she just said, “Poor things, why not? Maybe it'll make them more grateful to Our Lord for letting them be born in Italy.” To adults and older children, she would explain more fully about the marks.

“It was the custom for slaves, for the honour of their masters, to wear tattoos: designs or patterns cut into their bodies. Up to then I didn't have any, while my companions had lots, even on their faces and arms. Well, our mistress took a whim to make a ‘present' of this sort of decoration to those of us who weren't already tattooed. There were three of us.”

“A woman expert in this cruel art arrived. She took us to the porch, while the mistress stood behind us, whip in hand. The woman had a dish of white flour fetched, and another of salt, and a razor. She ordered the first one to lie down on the ground and two of the strongest slaves to hold her, one by the arms and the other by the legs. Then she bent over the poor girl and, using the flour, began to trace on her belly about sixty fine marks. I stood there, watching everything, knowing that afterwards they were going to perform the same torture on me. Once the marks were completed the woman took the razor and swish, swish, sliced along each mark she'd traced, while the poor girl groaned, and blood welled up from each cut. When this operation was finished she took the salt and rubbed it as hard as she could over each wound, so that it would go in and enlarge the cut, and keep the edges open. The agony and torment! The victim was writhing in pain, and I was shaking in anticipation.

“When the first girl was taken away to her sleeping mat, it was my turn. I didn't think I had the strength to move, but one glance at the mistress and her whip made me get down immediately onto the ground. The woman was ordered to spare my face, so she started off by making six designs on my chest and then about sixty on my belly, and forty-eight on the right arm. What it felt like I cannot put into words. I kept thinking, ‘This is it; I'm going to die', especially when she rubbed the salt into me. Covered in blood, I was carried to my sleeping mat where I lay semi-conscious for hours on end.

“When I came to, I saw beside me the other two who, along with me, had been made to suffer this atrocity. For over a month all three of us were condemned to lie there, stretched out on the reed matting, unable to move, without even a piece of rag to dry the pus which seeped continuously from the wounds kept half open by the salt. I've still got the scars. I can honestly say the only reason I didn't die was through a miracle of the Lord, who destined me for better things.”

Black Mother was quite clear that the way she had been treated was very wrong. She hoped very much for the situation she had known in Sudan to be changed completely, so that no one else would have to suffer as she had. Nevertheless she didn't hate those who had inflicted so much pain on her, and wouldn't have them demonized. When one Sister exploded in righteous indignation against “those wicked slave-owners” she placed a finger on her lips:

“Sshh … Poor things, they weren't wicked. They didn't know God. And also, maybe they didn't realize how much they were hurting me.”

On another occasion she smiled and said,

“I pray for them a lot, that Our Lord who has been so very good and generous to me will be the same with them, and bring them all to conversion and salvation.”

The Mahdi

Gordon's apparent success in suppressing slavery in Sudan had made good newspaper headlines in Europe, but he himself knew he was fighting a losing battle, and his efforts had infuriated many powerful groups. The fact that he was not only a foreigner, but also a Christian, could make it very easy to unite the different factions in an uprising against his authority. At the same time serious trouble was brewing in Egypt, where the country's modernisation along European lines had tied it very firmly into the global economy - an economy dominated by European capital. The Suez Canal had been built with Egyptian labour, but very soon the khedive was obliged to sell his shares in it to Britain, because his debts were spiralling out of control.

In 1879 Ismail was deposed in favour of his son, Muhammad Tawfiq, who ruled thereafter as a British puppet. An attempt by indigenous Egyptians to resume control over their own country was ruthlessly suppressed. When Gordon heard what had happened he resigned, so creating an abrupt power vacuum in Sudan.

Times of extreme crisis throw up apocalyptic expectations. In some parts of the Islamic world, the expectation can focus on a mahdi, or divinely-appointed leader. On Aba Island, in the stretch of the White Nile which flows along the border of Kordofan, a pious young sufi named Muhammad Ahmad grew convinced that he was the longed-for mahdi, called by God to set right a world which had gone astray. On 29th June 1881 he proclaimed a new creed: “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is the Prophet of God, and Muhammad al-Mahdi is the successor of God's Prophet!”

Comboni, visiting his missions in Kordofan at the time, was aware of the nascent revolt but attached little importance to it: the new Governor-General, Ra'uf Pasha, had sent troops to put it down. Returning to Khartoum he reported sadly, in response to an enquiry from Ra'uf, that slaving continued to flourish in the Nuba Mountains. In October several of his missionaries fell ill, and he helped look after them before succumbing himself. On 10th October he died.

Successive armies were sent against the Mahdi, but each in turn was defeated. Bakhita and her fellow-slaves were told nothing about what was going on, but they were aware that their master was away from home; he must have been involved in some of the failed campaigns. Certainly he could see the writing on the wall and, around the middle of 1882, decided to get out of Africa before it was too late.

“After an absence of several months, the General returned to Kordofan having made up his mind to return to Turkey. He set about making preparations for departure and, since he had a large number of slaves, he selected ten of them including me, and sold off the rest. We left Kordofan and after several days' journey on camelback we put up in an inn in Khartoum. There he put the word around to anyone who wanted to buy slaves. The Italian consular agent paid a call. I was told to bring him a coffee. I saw him examining me from head to foot, but never imagined he was planning to buy me. I only realized the next day, when the Turkish General told me to go with the consul's housekeeper to help her carry a package. This time I was really lucky, because the new master was so good and took a great liking to me. My job was to help the housekeeper with the domestic work.”

The countries of western Europe all maintained representatives in Sudan, and those which couldn't afford a professional diplomat arranged for part-time cover by one of their nationals already there on business. Calisto Legnani, who had already spent two years trading in gum-arabic, was appointed consular agent in 1880. He must have made frequent trips to El Obeid, and been personally acquainted with the Turkish General from whom he purchased Bakhita. It's a fair indication of the failure of the many attempts to suppress slavery in Sudan that even resident Europeans routinely bought and held slaves.

Legnani was a frequent visitor to the Catholic mission in Khartoum. Did this mean he took Bakhita there, or at least mentioned it to her? No, it didn't. Even someone who took the Catholic faith seriously might have hesitated to try to share it with his Sudanese servants, who were automatically assumed to be Muslims.

However, Legnani's visits to the mission did not indicate religious conviction. Every European in Khartoum visited the mission. The Italian traders attended Mass regularly, and were often pillars of the parish - even though in Europe they might never go inside a church, for they were all very gung ho for Italy's recently-won unity and independence, and such an attitude at that date usually went along with a sharp anti-Catholicism.

In Khartoum there wasn't much else to do, and dropping in at the mission gave them an opportunity to meet fellow-countrymen, and helped assuage their nostalgia for Europe. In Khartoum as in El Obeid, Bakhita remained completely unaware that there was a Catholic mission in the town, and she had still never heard a word about Christianity. Nevertheless Legnani proved a decent and kindly master, and she was very happy in his service. “There were no scoldings, no punishments, no beatings! I couldn't believe I was enjoying so much peace and quiet.”

For the missionaries in Kordofan, meanwhile, all peace and quiet was at an end: El Obeid was under siege by the Mahdists. The staff of an outlying mission at Dilling surrendered and were taken as prisoners to the Mahdi's camp, where repeated efforts were made to convert them to Islam.

The Austrian consul in Khartoum sent money to ransom them, but it was refused. Eventually, on 27th September, they were told that unless they converted they would be put to death the following day. The eight missionaries - priests, Brothers and Sisters - spent the night praying and writing goodbye letters to their families. At 9.00 am they were led out in front of the 40,000-strong Mahdist army, and ordered to kneel and bow their heads for the executioner's sword.

Just then the Mahdi rode up on a white camel and ordered a stay of execution, to give them one more chance. Taken before the Mahdist leaders, each was asked, “Which do you choose: Islam or death?” Each one chose death. Most of the leaders argued that they should be killed, but Khalid Ahmad al Omarabi declared that Islamic law forbids the execution of church persons who surrender without fighting. The Mahdi acknowledged that he was correct. However the missionaries remained prisoners, and were not allowed to leave the camp.

In January 1883 El Obeid surrendered. Thirty horse-men came to the mission, and carried off Bakhita Kwashe together with four other Sisters. They too were ordered to become Muslims, but refused. They were made to march with the army, barefoot over the hot sand, sharp rocks and thorn bushes of the desert, and at one point a Sister was hung upside-down and beaten on the soles of her feet.

To her relief, Bakhita Kwashe wasn't singled out to be treated any worse than the others, though as a Sudanese ex-slave she might have been considered technically an apostate from Islam. When the Mahdi heard how the nuns were being treated, he disapproved and ordered them brought into his own enclosure for safety. Later, some of the missionaries managed to escape and make their way to safety in Egypt; Bakhita Kwashe was one of those few. The rest remained prisoners for many years, living in harsh conditions in which half of them died.

For the moment the revolt appeared confined to western Sudan, and Calisto Legnani saw no cause for alarm. He spent several months during the second half of 1883 travelling: first to Italy and then, in connection with his promotion to Vice-Consul, visiting the port of Suakin on the Red Sea, before settling back into his main residence in Khartoum. Gordon returned to the city in February 1884 with orders - if no agreement could be reached with the Mahdi - to evacuate it. Believing that a safe evacuation was impossible, he resolved instead to try to defend it. From September it was under siege by the Mahdists.

Even as the year drew to a close, most inhabitants remained confident that the British army was on its way, and all would be well. However, when Bakhita heard that Legnani was planning another trip to Italy she took notice - not because she was frightened, and anxious to get out of the beleaguered city, but for another reason that she couldn't clearly explain:

“I don't know why, but when I heard him name ‘Italy', although I knew nothing of its beauty and charm, a keen desire sprang up in my heart to accompany my master. He liked me so much I dared to ask him to take me to Italy with him. He explained to me how long and expensive the journey was, but I insisted so much that he agreed, to please me. It was God who wished it, I realized later. I can still feel the joy I experienced at that moment. We set off. By ‘we' I mean the consul and his friend, a young black boy, and myself, riding on camels all together in a caravan. After a few days' journey we reached Suakin.”

Khartoum was by then virtually surrounded by rebel forces, but Legnagni and his friend, a fellow-businessman named Augusto Michieli, must have known a way for a small party to sneak through.

The fall of Khartoum

On the night of 25th January 1885, the Mahdi's forces crossed over the White Nile to mass around the southern ramparts of Khartoum, where a slight fall in the level of the river had exposed a sandbank. This foothold enabled them to breach the city's defences and, as the following day broke, take it by storm. Gordon was killed in the fighting, and many thousands of people - starting with the European residents and all identifiable Christians who refused to adopt Islam - were put to the sword.

Bakhita's knowledge of the event was limited to what her owners chose to mention to her:

“After about a month the consul and his friend received the sad news that a gang of rebels had entered the city of Khartoum, had destroyed everything, and taken possession of all the slaves. Since the consul and the other gentleman had been robbed of everything, they were very upset. If I had stayed there I would certainly have been stolen and what would have become of me? How much I thank the Lord for having saved me yet again! We stayed in Suakin for a month, then began our voyage by ship across the Red Sea and other seas as far as Genoa. There we took lodgings in a guesthouse whose proprietor was well known to the consul's friend, and had asked him to purchase a black boy for him. So the boy who had been my companion during the voyage was immediately made over to him. The friend's wife had come to meet him and, seeing us two blacks, said she wanted one and asked her husband why he hadn't brought one for her and her little daughter. The consul, to please his friend and her, made a present of me to them.”

Legnani and the Michielis were all making for destinations in the Veneto region, on the opposite side of the Italian peninsula from Genoa. Probably they covered this last leg by train, but at a certain point the party broke up:

“The consul headed for Padua, and I never heard anything more of him. My new master and mistress and I made our way to Mirano Veneto where, for three years, I was nurse to their little daughter.”

Mirano is a small town a short distance inland from Venice, and the Michielis' family home stood in an outlying village named Zianigo. Bakhita's account, which was only written down years later, slides over a detail: Michieli's wife Maria Turina had a son of about five, and had given birth to a baby girl the previous summer - but this girl died very young and Bakhita never mentions her. The daughter she did look after was not born until February 1886. Magnificently named Alice Alessandrina Augusta, she was known to Bakhita by her pet-name Mimmina.

“The baby came to love me dearly, and I naturally came to feel a similar affection for her.”

Shortly after Mimmina's birth Augusto Michieli returned to open a hotel in Suakin. The Red Sea port still remained in Egyptian hands: whether because Britain was prepared to defend it more effectively than Khartoum, or perhaps because the Mahdists were never all that interested in taking it so long as they could control its hinterland, it never fell to the insurgents.

Bakhita, together with the rest of the Michieli family, remained in Zianigo; only at the end of 1886 did Augusto send for them all to come out and join him. During their absence the empty house, with the small farm attached to it, would be left in the hands of the Michieli's local agent Illuminato Cecchini.

Farewell to Africa

“After three years had gone by I returned with the mistress to Suakin in Africa, where her husband was running a large hotel. We stayed for around nine months, after which the master decided that the whole family should make their permanent home there. However the mistress would have to return to Italy to sell off the property and pack up the furniture. I was supposed to stay meanwhile at the hotel with the baby, but my mistress didn't fancy travelling on her own, so it was agreed that we should both go with her. Then I bade in my heart an eternal farewell to Africa. An inner voice told me I would never see it again.”

The return to Zianigo took place in the autumn of 1887. Maria Turina duly set about selling the house and land - naturally taking advice from Cecchini. The agent's visits to the house led to some friction, as he was shocked to realize that Bakhita had never been offered religious instruction. He persuaded the Michielis' housekeeper to say prayers with the African girl each morning.

It's unlikely that the housekeeper's devotions, whether rattled off in Italian or in Latin, meant anything to Bakhita, but the arrangement certainly annoyed their mistress. If Augusto was fundamentally irreligious, Maria Turina was more so. She wasn't Italian but Russian, daughter of a wealthy St Petersburg family and, although nominally Orthodox, like many upper-class Russians of the time she claimed to be an atheist. She didn't want Cecchini, as she saw it, “upsetting the servants”.

The Michielis belonged to that well-heeled class for whom Italian reunification and independence had brought solid benefits. By contrast Cecchini, son of a village cart-maker, was essentially a peasant. He knew only too well that in the new Italy, conditions for the rural poor had deteriorated - and it was a matter of deep concern for him even though he, personally, was not too badly affected. He viewed his employers' fashionable superficiality about spiritual values with instinctive scepticism, and quietly set about subverting it.

Giuseppe Sarto, Pope St. Pius X

Although he'd never had much formal education, having left school early to help his father in the workshop, he had plenty of native intelligence and a mind of his own. He was deeply religious, and in his home parish of Salzano used to play the organ in church. He got on specially well with the parish priest assigned to Salzano in 1867, Fr Giuseppe Sarto, a remarkable priest unreservedly dedicated to his pastoral and charitable work; he and Cecchini used to play cards together. They kept in touch even after Cecchini's marriage in 1870, when he moved to Zianigo to make a career as a middle-man and business agent for the local farmers and small landlords. He was well-known locally as a source of excellent advice, which was free for those in trouble, and he was very active in promoting self-help schemes such as savings banks and mutual assurance societies.

It took Maria Turina a whole year to sell off the property, and even then there were still some bits of business which couldn't yet be finished. She was missing her husband, so she decided to take a break, travel out to Africa and spend some time with him. Since she wouldn't be there long, it hardly seemed worthwhile to drag the baby out with her.

She laid her plans before Cecchini: could he suggest somewhere suitable for Bakhita and Mimmina to stay during her absence - preferably a boarding school where Bakhita could receive some education? (What she had in mind by education, and whether it was realistic given that Bakhita was nearly twenty and had never previously had any schooling, is not clear.) Cecchini knew just the place: the Catechumenate in Venice. It was run by the Canossian Sisters, the same congregation which had a house in Mirano. Maria Turina must know how eminently respectable they were: they could certainly be trusted to ensure the two girls were properly looked after.

The Catechumenate

Since Vatican II the term “catechumenate” has made a comeback: many Catholics today would recognise it as a process of Christian initiation. Probably to Maria Turina, however, the term meant nothing and - although her husband was a scion of the Venetian patriciate - she herself was unlikely to have known the history of the Catechumenate. It had been set up in 1557 purposely to house adult non-Christians wishing to receive instruction in the faith. Because such individuals were often rejected by their communities of origin and faced the loss of home, family and livelihood, the institution offered them shelter, and practical help in beginning a whole new way of life. Venice's wide-spread trading contacts and comparative religious toleration made it a meeting point of cultures, and the flow of converts remained impressive for well over a century.

Although the Catechumenate never achieved the security of lavish endowments, it enjoyed a certain social cachet which attracted interest and donations from the patriciate and, after beginning operations in rented premises, moved to a permanent site on the edge of the city. Twice the premises were rebuilt, each time on a larger and grander scale: there were separate sections for men and women, with a small church dedicated to St John the Baptist standing between.

But after Napoleon crushed the independence of the Venetian Republic, the magnificent buildings fell into disuse. The Canossian Sisters had been asked to take over the women's section in 1848. They did run a school on the premises, though it was actually a day school for poor girls from the neighborhood. They also maintained the historic links of the institution with the city's aristocracy, by organizing prayer meetings and conferences for society ladies. Strictly speaking, they had no boarding school facilities. But naturally, if ever the opportunity arose, they would be more than happy to fulfil the Catechumen ate's original purpose by offering religious instruction to prospective converts.

Cecchini took it upon himself to negotiate the arrangements. Once he had explained the situation, the Sisters readily agreed to take Bakhita, but there was a technical difficulty about Mimmina. If she'd been unbaptised they would happily have stretched a point and put her down, as they planned to do with Bakhita, as a candidate for instruction, though she was not yet three.

But the Michielis' irreligion was purely conventional and their children were all baptized. Maria Turina would not agree to separate arrangements being made for the two girls: they must be kept together. She expressed willingness to pay for their board and lodging, but since she was about to leave the country it might be difficult to hold her to this. Resolving the difficulty took a whole month, during which Cecchini visited the Michieli house frequently.

One day he gave Bakhita a small silver crucifix.

“Giving me the crucifix he kissed it with devotion, then explained to me that Jesus Christ, Son of God, died for us. I didn’t know what it was, but impelled by a mysterious force I hid it in case my mistress took it off me. Before then I had never hidden anything, because I was never attached to anything. I remember how I used to look at it in secret, and feel inside myself something I couldn't explain.”

“That is your home now”

Not until the very end of the year did Maria Turina, together with Illuminato Cecchini, his wife and his five children, escort Bakhita and Mimmina to Venice and install them in the Catechumenate. To make sure his carefully laid strategy didn't fall through, Cecchini had personally guaranteed to defray all expenses involved in looking after both the girls, if the Michielis defaulted.

“When my mistress accompanied me to the institute, she turned round on the doorstep to bid me goodbye and said: “There, that is your home now.” She said this without having any idea what she was really saying. Oh, if she had realized what was going to happen, she'd never have brought me there!”

Wide-eyed, Bakhita was led into the large, cool building and up a spiral staircase, above which the ceiling was painted to depict the Baptism of Christ.

“I was entrusted, together with the baby, to a Sister who was well-experienced in instructing catechumens, Maria Fabbretti. Tears come to my eyes whenever I think of all the care she took of me. She asked if it was my desire to become a Christian and, hearing that I did desire it and was come with that intention, she was filled with joy. Then those holy Mothers instructed me with heroic patience, and brought me into a relationship with that God whom, ever since I was a child, I had felt in my heart without knowing who he was.”

Bakhita stressed the patience of Sister Fabbretti and her fellow Canossians because she knew it hadn't been easy for them. She was obedient and co-operative as ever, and eager to learn, but she could speak only a broken mixture of standard Italian and the Veneto dialect. It was very difficult for her to understand properly what was said to her, unless it related to practical matters immediately to hand. Everything had of course to be conveyed verbally, or through pictures; the instruction sessions could never be supplemented by giving her material to read later.

Not long after their arrival she and Mimmina were spotted from the balcony of a house just opposite by six-year-old Giulia Della Fonte, who began coming over each morning to play with the baby. Giulia was fascinated by the black nursemaid of whom Mimmina was clearly so fond. Bakhita was always smiling - and yet there was something odd about the smile: it was a kind smile, but it wasn't a happy one. Why was Bakhita so sad inside?

Unfortunately, there was no way of finding out: Giulia could hardly understand anything she said. Since the time she arrived at Legnani's house in Khartoum, Bakhita would have said she was happy. But deep inside, her spirit remained painfully crushed by her horrific experiences and, even though her circumstances had changed so dramatically, she couldn't just shrug off the memories. Nevertheless, the hope had begun to dawn in her that a healing of her spirit might be possible.

Bakhita soon realized that whether or not other people understood her, she could always talk to God who understood everything, and didn't even require words. When left to her own devices, even while keeping an eye on Mimmina, Bakhita made the most of her opportunities for prayer. She often spent time in front of the large crucifix in the downstairs parlour. There was also the domestic chapel, where a statue of Our Lady of La Salette had been installed making it into a minor pilgrimage centre, or St John the Baptist next door. Alternatively, with Mimmina skipping along beside her, she could take a little walk round to Our Lady of Health, a church whose dome she could see from the window of their room. In that church there was an old icon of the Madonna and Child brought from Crete by the evacuated garrison when the island, a Venetian colony since the Fourth Crusade, was surrendered to the Turks in 1670. As in so many of Europe's most venerated Marian images, the figures depicted in it were black.

“No”

The best part of a year went by as if in a lovely dream, until on 27th November 1889 Maria Turina turned up again. All her business had been settled, and it was time now for Mimmina and Bakhita to travel back with her out to Africa, this time for good; Bakhita's new job behind the hotel bar was waiting for her in Suakin. And it was then that Bakhita said no: she wasn't going.

“I refused to go with her to Africa because I was not yet well-enough instructed to be baptized. I also thought that, even if I had been baptized., it wouldn't be easy to practise my new religion there, and therefore it was better for me to stay with the Sisters.”

Never before in her life had Bakhita flatly refused to obey an order. Maria Turina went through the roof. She raged and stormed at Bakhita, reminding her of all the Michielis had done for her, pointing out all the arrangements that had been made on the assumption that she would continue to be part of their household, and threatening her with dire consequences if she was so silly as to upset everything.

In the nineteenth century it was generally assumed that, for any young woman, to dare to make her own life decisions was both wrong, and dangerously foolish: she must defer to her parents or, in the case of a servant with no family of her own, her employers. Behind this assumption lay a harsh reality: as with domestic slaves in African societies, the shelter even of an exploiting household was usually a far better option than any of the likely alternatives.

Bakhita didn't feel in the least indignant at Maria Turina's attitude; on the contrary, she saw it as largely justified. If the Michielis had been cruel masters the issue might have seemed more clear-cut, but they weren't; they really had tried to do what they thought was best for her. Also, she was emotionally attached to the family, and positively adored Mimmina. Every accusation went through her like a knife. Feeling horribly torn apart, again and again she was on the point of giving in. What stopped her was not the belief that she had the right to do what she wanted with her own life, but the recognition that she owed a higher loyalty to God.

Eventually Maria Turina stormed out. Exhausted, Bakhita went down to the parlour and spent a long time praying in front of the crucifix there.

“It made me suffer to see her so disgusted with me, because I really liked her. It was Our Lord who gave me strength to be so firm about it, because he wanted to make me his. How good he is!”

Her ordeal wasn't over. Next day Maria was back, together with a lady friend, someone clearly very rich and important. Together they resumed the attack, alternately pleading and threatening. Still Bakhita wouldn't give in, and after they'd gone she was back praying in front of the crucifix.

Patriarch and Procurator

By now everyone in the Catechumenate knew about the row, which was creating tremendous embarrassment. The Sisters, although they liked Bakhita and would have loved to keep her with them, tried to persuade her to do what Maria Turina wanted. But she insisted:

“No. I won't leave the House of Our Lord. It would be the ruin of me.”

What could she mean by that? After being excluded from the rest of Sudan, the Verona Missionaries had established a mission in Suakin, so it wasn't a place without any Catholic presence or access to the sacraments. Moreover the Mahdist regime itself had been defeated and overthrown by Lord Kitchener the previous year, bringing Sudan under British rule. There seemed no obvious reason for Bakhita to be so dead set against returning to Africa. Why give up the prospect of a secure home and job for life, and alienate the wealthy family which had offered her their protection? For her to stay in the Catechumenate might be no problem for the next year or so, but what about her long-term future? However Bakhita instinctively knew that she would not be capable of living, in its fullness, the Christian life to which God was calling her in baptism, if trapped in the profoundly unsupportive environment of an irreligious household in a non-Christian country.

Behind all other considerations lay the basic question of Bakhita's legal status: did the Michielis legally own her? Fr Jacopo, the elderly aristocratic priest who was Rector of the Catechumenate, didn't know what to do. When Bakhita, despite everything, persisted in her refusal, he decided to seek advice from higher up and wrote to the Patriarch of Venice, Domenico Agostini. The Patriarch in turn sought an opinion from the Royal Procurator, who replied categorically that slavery did not exist in Italy: therefore Bakhita was free, and could not be compelled to return to Sudan. Maria Turina herself approached the Procurator, but got the same response.

On the third day, 29th November, a summit meeting was held in the parlour. Maria Turina arrived flanked by the lady friend who'd come before, and a male relative wearing the impressive uniform of an army officer. The Patriarch was there, the Priest-President and the Mother General of the Canossian congregation, Fr Jacopo and some of the Sisters who worked in the Catechumenate. The government authorities were represented by the Procurator and the Prefect.

“The Patriarch spoke first. There followed a long discussion, which concluded in my favour. Mrs Turina, weeping with rage and disappointment, seized the child who didn't want to be separated from me, and was clinging to me to try to make me come. I was so upset I couldn't say a word. I left them weeping and went out, satisfied that I hadn't given in.”

Next morning Giulia Della Fonte danced in as usual to find Bakhita sitting alone in floods of tears. Mimmina had gone away to Africa, and she would never see her again.

Baptism

Bakhita was baptized in the Church of St John the Baptist on 9th January 1890. Illuminato Cecchini and his family were the first to arrive, and little Giulia was there with her mother and aunt. Besides this handful of personal contacts, the flower of the old Venetian nobility turned out for the occasion. At the request of his devout but bedridden wife, Countess Giuseppina, and perhaps also of his relative Fr Jacopo, Count Marco Avogrado di Soranzo stood godfather, and Lady Margherita Donati was godmother.